This month, the Department of Transportation fined Jet Blue airlines $2 million for what it described as “multiple chronically late flights.” They penalized Frontier Airlines for the same reason. They also are suing Southwest Airlines for chronically delayed flights, based on how they unrealistically scheduled some flights that unavoidably led to delays.

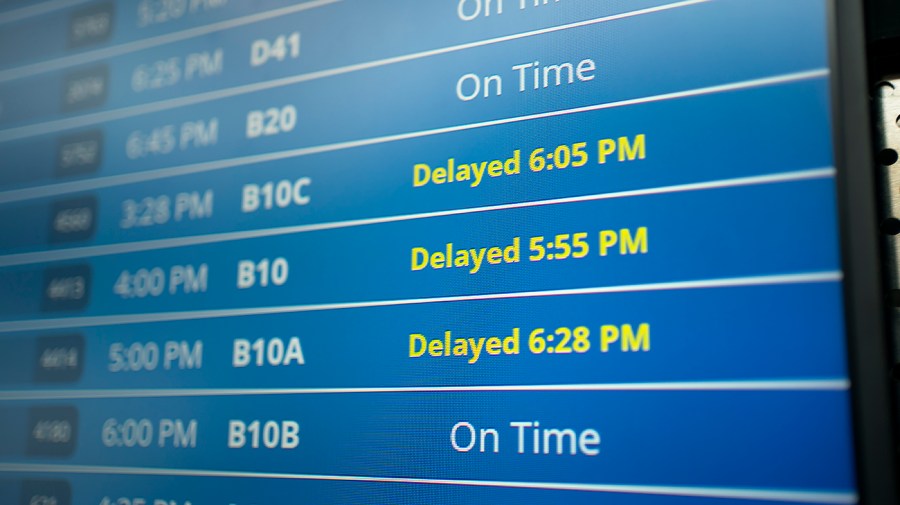

Anyone who has sat in an airport gate area or, worse yet, on an airplane at the tarmac waiting to depart understands the frustration felt with flight delays. But before bashing Jet Blue and other airlines about flight delays, it is worth looking at the cause of flight delays and what can be done to better serve passengers.

The Department of Transportation defines a flight to be chronically delayed if it is “flown at least 10 times a month and arrives more than 30 minutes late more than 50 percent of the time. Cancellations are included as delays within this calculation.”

By this definition, a flight delay occurs when flight does not reach its final destination within 30 minutes of its scheduled arrival. Airlines set their schedules, which includes when a flight is set to depart and when it is set to arrive. This includes the time it takes to taxi from the gate to the runway and the time once it lands to taxi to its gate.

Airlines are motivated to build some slack into their schedules. This gives each flight some buffer to absorb any unexpected delays, either on the ground or en route to its final destination. If the airlines do not build enough buffer into a flight, they are susceptible to a poor delay record. If they build too much into the schedule, the planes will be chronically early, which means they may need to wait on the tarmac for their arrival gates to become available.

Given that many airlines use a hub and spoke system, flights arriving into a hub must be scheduled to give passengers sufficient time to catch their connecting flights. Anyone who flies regularly knows that a delay into a hub can mean a missed connection and an extra wait for the next flight.

Certainly, how flights are scheduled contributes to flight delays. Yet there is so much out of airlines’ control that using the Department of Transportation measure for “chronically late flights” misses what are the primary causes of flight delays.

The single biggest cause of flight delays is weather. When inclement weather moves into an area, particularly around a hub airport, the best laid schedules can get instantly upended. Flights both departing and arriving get disrupted, creating schedule chaos. Flight crews that are out of position must be reconfigured in real time. Since flight crews are certified to only fly a certain type of airplane, they cannot be easily moved between Boeing and Airbus airplanes.

Then there are flight crew rest requirements and restrictions. Pilots and first officers can only fly a certain number of hours per year, per month, over any seven consecutive days, and within any given 24-hour period. Once their flying clock runs out, flights must be cancelled or alternate flight crews must be found. This becomes particularly problematic in a month with numerous weather delays early in the month. If additional weather delays hit later in the same month, many flight crews may time out simultaneously, the “perfect storm” for flight delays and cancellation.

The ”800-pound gorilla” surrounding the issue is air traffic control. Air traffic control delays have been well documented, particularly in the Northeast corridor. Airlines are at the mercy of the air traffic control system, and for good reason — their primary role is the safety of every flight in the air system. When air traffic control limits arrival and departure volume, airlines must abide by their directives, even if it means flight schedules cannot be met.

What all this means is that although airlines operate and schedule flights, there is so much out of their control that penalizing them for “chronically delay fights” is not an appropriate response from the Department of Transportation. It is like buying size 6 dresses for a woman who can only fit into a size 14. Just giving her the smaller dress size does not mean that she is able to fit into it, or that she will change her behavior to fit into it.

To get airlines to serve passengers better, the first step is to improve air traffic control so that it is less likely to be the cause of flight delays and disruptions. Safety must always be the top priority for air traffic control; allowing flights to operate in unsafe conditions is not the solution. However, providing the necessary resources and personnel to not be the cause of delays is well within their rubric.

Second, adjust the definition of “chronically late flights” to include only “chronically delayed flights within airlines’ control.” This would include mechanical delays and delays due to poor scheduling practices (including why Southwest Airlines is being sued). How flights are scheduled across multiple airlines may also force too many flights into an airport’s airspace over a given time period that the airport cannot absorb even under the most ideal conditions.

Along these lines, provide a benchmark time for every flight between Point A and Point B. Use that as the standard for determining whether a flight is delayed, which AI algorithms can be built to provide. This means that every major airport is included in the flight delay calculus, possibly even including weather and computer disruptions on each day around each airport involved. This provides an objective way to measure when extraneous circumstances are causing delays. Otherwise, the airline operations are at fault, independent of the time allotted in airline flight schedules.

Such changes should be the beginning, not the end, of the discussion on flight delays. Using blunt penalties to discourage airline flight delays is misdirected. As the Department of Transportation resets with a new secretary this is the time to right-size airline scheduling and work toward a solution that serves the best interests of all passengers.

Sheldon H. Jacobson, Ph.D., is a professor in computer science in the Grainger College of Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He used his expertise in risk-based analytics to address problems in public policy.