I am an early American historian. I have spent decades studying and writing about the history of our country and its remarkable people. The current cultural climate is filled with historical consciousness, but also with widespread misunderstandings and misrepresentations of history.

One of the most striking aspects of this moment is the pervasive sense of instability. Many Americans feel an anxiety that is difficult to describe, a visceral apprehension about what comes next.

As historians, we are often distanced from this sensation because we know how past events turned out. But living through history in real-time makes that sense of unpredictability palpable in a way that is rarely captured in historical narratives.

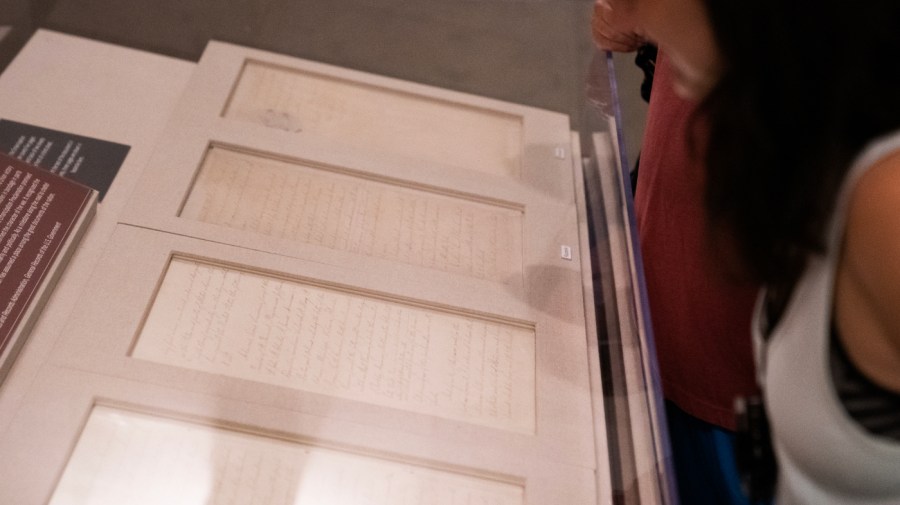

Adding to this uncertainty is the intense battle over our national narratives and historical identity. I have witnessed, with growing concern, the dismissal of the national archivist and key leadership at the National Archives — an institution responsible for safeguarding our historical records and playing a crucial role in presidential elections.

I have also seen the troubling erasure of history from public spaces, particularly online. Websites containing information about the Tuskegee Airmen, Black American heroes, women’s history and transgender figures in the Stonewall Rebellion have been quietly removed.

Even references to the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945, were scrubbed from government web pages due to politically motivated keyword searches that apparently disregarded content.

More personally, I recently discovered that my own writings had been removed from National Park Service websites. Over the years, I was invited by the service to educate staff nationwide on how to present complex and difficult histories in ways that engage the public.

My contributions included essays and presentations on LGBTQ life in early America and gender-based violence, offering historical context to help park staff address these topics with nuance. That work has now apparently been erased.

My professional organizations, including the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association, have spoken out against these developments. Their statements highlight the historical significance of these changes and the urgent need for vigilance in protecting the integrity of historical scholarship.

I am deeply worried about the future of history as a profession. Graduate programs are rescinding acceptances, funding is disappearing and the next generation of historians is being undermined.

A government that funds historical research serves all of us; without it, we are left at the mercy of political operatives, pundits and fiction writers who reshape history to fit their own agendas.

Last week, the administration declared through an executive order, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” that the vice president would be overseeing a comprehensive sweep of the content at the Smithsonian museums, one of the world’s premier academic museum institutions.

The purpose of the initiative is to ensure that the content is acceptable to the government. The order made specific mention of unacceptable content on display at the Museum of African American History and Culture and included a prohibition for the Women’s History Museum against the inclusion of transgender women.

As a historian of America’s founding, I am acutely aware of what lies ahead as the country approaches the 250th anniversary of its independence. This anniversary will likely be politicized to an extent unseen since the post-Civil War period, when revisionist narratives about enslavement gained traction in a nationwide propaganda campaign.

I recall when Trump’s 1776 Commission and the proposed “Garden of Heroes” were announced, and I expect these ideas to resurface in an attempt to frame history in ways dictated by politicians rather than scholars. We should not turn away from our own histories or overlay a sanitized, artificial version of the past that aligns with present-day political agendas.

History is meant to be debated and revised. Professional historians engage in rigorous discussions within scholarly frameworks that rely on evidence and interpretation. Censoring content for political reasons, confusing monuments with actual history and treating opinions as facts will only lead us further into misinformation and mythmaking.

History also offers perspective. “This too shall pass” is a lesson many of us have heard since childhood. This does not mean we should sit idly by and wait for this period to pass. Rather, understanding that we are part of an ongoing historical narrative should both humble and empower us. We are all agents of historical change, and the future is unwritten.

History helps us imagine new possibilities — alternative ways of structuring society, radically different ways that previous generations lived and inspiring moments of resilience and transformation. It can be a source of motivation and vision.

However, we cannot change the past, nor should we try to erase or distort it. A nation that denies its rich and diverse histories makes itself weaker, not stronger.

The work of historians is essential, not only for understanding where we have been but also for charting a path forward that is informed, inclusive and true.

Thomas A. Foster is a professor of history at Howard University. His most recent book is “Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men.”