CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA—Maryland governor Wes Moore, who is widely expected to seek the 2028 Democratic presidential nomination, has a powerful family story of racial injustice that he repeatedly tells during public speeches: His grandfather, as a small boy, fled 1920s Charleston with his family in the dead of night after his father—a prominent black minister and Moore’s great-grandfather—angered the Ku Klux Klan with sermons condemning racism. Narrowly escaping a lynching, the family took refuge in Jamaica. But Moore’s grandfather, just six years old at the time, vowed to return to America, where he eventually raised a grandson who made history in 2022 by becoming Maryland’s first black governor.

It’s a story straight out of Hollywood, and it was a central feature of Moore’s 2022 campaign stump speech, in which he described a version of American patriotism wherein “loving your country does not mean lying about its history.” Moore first told the tale of his exiled grandfather in a 2014 memoir and has since retold it countless times as he seeks to reclaim patriotism for the Democratic Party and to contextualize his own unlikely rise to power.

But there’s a problem with Moore’s story: It’s flatly contradicted by historical records and is almost certainly false.

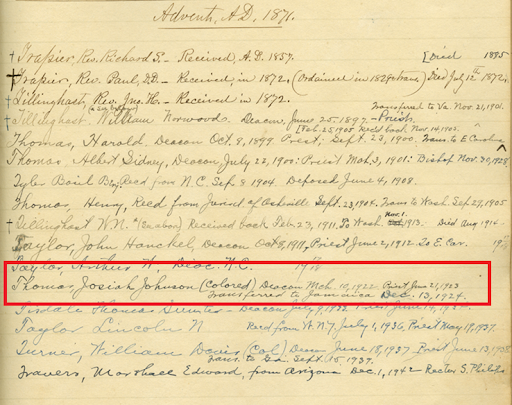

Moore’s great-grandfather on his mother’s side, the Rev. Josiah Johnson Thomas, did preach in the 1920s at a church in Pineville, S.C., about 65 miles north of Charleston. But historical records housed at the archives of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of South Carolina undercut the three main elements of Moore’s story—that Thomas suddenly fled the country in secret, that he was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan, and that he was a prominent preacher who spoke from the pulpit against racism.

Detailed church archival records, as well as contemporary newspaper coverage, indicate that Thomas, a Jamaica native, on Dec. 13, 1924, made an orderly and public transfer from South Carolina to the island of his birth, where he was appointed to succeed a prominent Jamaican pastor who had died unexpectedly a week earlier, on Dec. 6, 1924. Amid the copious documentation of the life and career of Moore’s great-grandfather, there is no mention of trouble with the Klan, which operated openly in 1920s South Carolina but never had a chapter operating out of Pineville, according to Virginia Commonwealth University’s Mapping of the Second Ku Klux Klan.

Many families tell larger-than-life stories about their forebears that wouldn’t hold up to scrutiny. But your typical family-tree fabulist isn’t preparing to run for president. And Moore’s fantastical tale of his great-grandfather’s escape from the Ku Klux Klan to exile to Jamaica adds yet another asterisk to his remarkably inflated résumé—about which the press have asked him very little.

Moore falsely claimed that he was born and grew up in Baltimore, which he did not; that he was inducted into the Maryland College Football Hall of Fame, an organization that doesn’t exist; that he received a Bronze Star for his service in Afghanistan, which he had not; that in 2006 he was considered a foremost expert on radical Islam based on his graduate thesis, which he never submitted to Oxford University’s library and can no longer locate; that he was a doctoral candidate at Oxford in 2006, a claim he has no documentation to support and on which Oxford refuses to comment; and that he had “a difficult childhood in the Bronx and Baltimore” despite attending New York City’s elite, private Riverdale Country School—where John F. Kennedy went to school—as a child and not living in Baltimore until college, when he attended Johns Hopkins University, another elite private school.

Moore’s story about his grandfather may be 100 years old, but for centuries, churches, including those that served poor communities, have kept detailed records about their congregants and, even more so, about their clergy. Moore’s great-grandfather, referred to as the “Rev. J.J. Thomas” in contemporary reporting, served as a clergyman at the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer in Pineville, S.C., under the South Carolina Colored Convocation, according to the annual directories of the Episcopal Church. Based about 60 miles north of Charleston, Thomas worked at the church from 1922 to late 1924, following an eight-year stint preaching at various Presbyterian churches throughout South Carolina and Georgia.

But from there, Moore’s narrative falls apart. During an appearance on Andrew Yang’s podcast in 2020, Moore said the Ku Klux Klan ran his grandfather and “the rest of my family out of this country, not just out of Charleston, South Carolina.” Time added to the narrative in 2023, reporting that Moore’s great-grandfather was “targeted for lynching,” making the governor “well acquainted with the case against America.” Moore said in a May commencement speech at Lincoln University, a historically black college in Pennsylvania, that his grandfather was “chased away by the Ku Klux Klan” because “my great-grandfather was a vocal minister in the community.”

“Being Black and outspoken was a crime—even if it wasn’t on the books,” Moore said. “So, in the middle of the night, they fled. My grandfather may have been just a boy… but he never forgot what happened that night.”

Episcopal Church archival records tell a different story. They show that Moore’s great-grandfather was “transferred” from the church he worked at in Pineville, S.C., to Jamaica—then a British colony—on Dec. 13, 1924, to take over for a Jamaican priest who had died. There is no suggestion that the move was hurried or secret, as Moore has stated. Jamaica was a natural fit for Moore’s great-grandfather, who was born on the island in 1880 and held a government-appointed post as a marriage officer in 1914 before his decade-long stay in the United States.

The Episcopal Church’s 1926 annual directory reported that Thomas was one of 12 clergymen transferred from the United States to foreign dioceses in 1925. Thomas’s transfer indicates he completed a formalized process that required the approval of several parties within the Episcopal Church.

“Typically, when a clergy member moves from one diocese to another, it is at the request of the clergy member, who works in concert with the new parish,” Amy Evenson, an archivist at the national Episcopal Archives in Austin, Texas, told the Washington Free Beacon. “All parties must agree that the move is advantageous, which is then approved by the Bishop.”

Evenson said the national Episcopal archives don’t have any records showing why Thomas was transferred to Jamaica. Reporting by the Daily Gleaner—then and now the paper of record in Kingston—shows, however, that Thomas returned to Jamaica to take over for a prominent pastor who had died a week earlier.

The Rev. George Lewis Young died unexpectedly in his home on Dec. 6, 1924, the Daily Gleaner reported. Young’s funeral was attended by 3,000 dignitaries from across the island, and he received tributes from officials at the highest levels of Jamaican politics, including the then-colony’s governor and members of its Legislative Council.

A few months later, on May 18, 1925, the conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Jamaica appointed Thomas to serve as Young’s successor, the Daily Gleaner reported. Moore’s great-grandfather made no mention of the Ku Klux Klan or any sort of dramatic escape from America when he spoke to the newspaper about his return to Jamaica. The paper reported that Thomas “laboured in the States for a number of years, and like many other Jamaicans he has returned to his native land to work among his people.”

Moore’s great-grandfather hit the ground running in Jamaica. The island’s governor appointed him to serve once again as a marriage officer, the Daily Gleaner reported on May 29, 1925.

The historical record lacks any evidence to support Moore’s claim that the KKK targeted his great-grandfather because of sermons decrying racism. Then-South Carolina bishop William Guerry, best known for his work to advance racial equality in South Carolina, reported to the National Council of the Episcopal Church in 1924 that the white community in Pineville, S.C., held the church where Thomas preached in high regard for the work it commissioned for the black community.

The Church of the Redeemer secured the services of a trained graduate nurse who “has attracted and won the confidence of the white people of the neighborhood” for the medical services she provided to “the sick and needy Negros of that community,” Guerry wrote, in Thomas’s final year before his transfer to Jamaica.

Guerry knew Moore’s great-grandfather personally. Archival records show he oversaw Thomas’s ordination to the priesthood in 1923.

And in 1925, shortly after Moore’s great-grandfather’s departure from the United States, Guerry reported that the “colored work” at the Pineville church “is in a most prosperous condition.” He gave no indication that Klan activity impeded its operations, hailing the diocese’s opening of an accredited industrial school elsewhere in the state as “the most progressive step that the diocese has ever taken for the moral and spiritual uplift of the Negro race in this state.” Guerry’s reports on Thomas’s church give no indication that one of the few black pastors in his diocese had been targeted by the Klan or had to flee the country, as Moore has stated.

Reached for comment, a spokesman for Moore, Ammar Moussa, accused the Free Beacon of being ignorant of basic history for daring to question Moore’s narrative. Moussa has responded to previous inquiries about Moore’s record by arguing that the Free Beacon is not “engaged in journalism.”

“The Free Beacon‘s fixation on Governor Moore is mildly amusing,” Moussa said. “What’s more concerning is how casually they treat the reality of being Black in the South in the 1920s. Anyone questioning whether racial terror and intimidation were pervasive in that era should open a history book or, better yet, reach out to the KKK to ask what they were up to in South Carolina in the 1920s.”

Moore’s great-grandfather lived in South Carolina during the height of what’s known as the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, a politically active organization that operated openly throughout the country from 1915 to 1940.

Virginia Commonwealth University history professor emeritus John Kneebone, a scholar of the second Ku Klux Klan, said the Klan of the 1920s is best defined as an organization of vigilantes who primarily targeted white people and were largely focused on bootleggers engaged in the illegal production of alcohol during Prohibition.

“The Klan was focused on the moral behavior of white folks,” Kneebone told the Free Beacon. “Certainly, there was violence directed at blacks, but that comes out of continuing racist conflict, the lynchings and other things that were present before the Klan and continued after that.”

Kneebone said it’s certainly plausible that the Klan ran Moore’s great-grandfather out of South Carolina because it took offense to his preaching. Equally plausible, he said, is that “someone got in touch with him and said, ‘Come here and when Reverend So-and-So passes, you’ll be his replacement,'” Kneebone said. “We just don’t know.”

The second Klan saw its membership swell to millions by the mid-1920s and made no secret about its opposition to blacks. Still, its primary victims during that era were whites suspected of engaging in “immoral behavior,” according to a 1984 article in the South Carolina Historical Magazine. The piece examines the Klan’s activities between 1922 and 1925 in Horry County, about 90 miles northeast of Pineville, where Moore’s great-grandfather preached.

“In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan counted blacks and Jews among its sworn enemies, but Klansmen attacked few members of either group,” the article states, adding that the Klan’s “victims were usually native whites who had violated the community’s moral code: prostitutes, bootleggers, wife-beaters, and adulterers.”

A third Ku Klux Klan emerged in the 1950s, in which “race, not morals, was its main concern,” according to the report.

Moore’s director of communications, David Turner, declined to name any members of Moore’s extended family who could speak to his great-grandfather’s escape from the Klan.

“They have no desire to teach you the basics of American history,” Turner told the Free Beacon.

The Free Beacon visited historic archives in Charleston to delve into the history of Moore’s family in South Carolina and retraced the travels of Moore’s great-grandfather in the United States, starting from his initial arrival in 1906 through his final return to Jamaica in 1924. None of the records indicate he ran into any sort of trouble with the Klan or that he was considered a prominent preacher on the subject of racial equality, as Moore claims.

Moore’s great-grandfather first arrived in the United States in 1906 to attend Lincoln University’s theological seminary. He graduated in 1910, with Baltimore’s Afro-American newspaper reporting that he intended to return to Jamaica to devote his time to teaching among his own people. Thomas did just that, preaching as a Presbyterian minister in Jamaica (and working as a governor-appointed marriage officer) until 1914.

He returned to the United States on March 3, 1914, arriving on Ellis Island with the intention of meeting up with the Rev. Quintin R. Primo, a Presbyterian minister based in Fleming, a town in Liberty County, Ga., according to his arrival manifest. County records show Thomas got married in the town in October 1914, and by the end of that year, he obtained a post as a minister at the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Atlanta, according to minutes of the Synod of Atlantic in 1914 and 1915. While living in Georgia, he had his first child, a daughter, according to 1920 census records.

From there, Thomas made his way to Fountain Inn, S.C., where Moore’s grandfather, James Thomas, was born in October 1918, according to his birth certificate. Moore often claims his grandfather was born in Charleston, 250 miles southeast of Fountain Inn. Charleston is an important Democratic stronghold in South Carolina, a state whose Democrats have voted for the eventual Democratic presidential nominee in every contested primary since 2008. Moore now blames his mother for misinforming him about the location of his grandfather’s birth, the New York Times reported in May.

Thomas was still working for the Presbyterian Church as a school teacher at Fountain Inn in 1921, church records show. But for reasons unknown, Moore’s great-grandfather soon left the denomination for the Episcopal Church.

“We have added by ordination to the Diaconate the Rev. J.J. Thomas (colored), who came to us from the Presbyterian Church, North, and who is now at work at the Church of the Redeemer, Pineville,” the Council of the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina reported in May 1922.

Located in the archives of the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina is a handwritten note from Moore’s great-grandfather, dated Jan. 14, 1922, in which, as part of his examination for the Episcopal priesthood, he explained the differences between the Presbyterian and Episcopal Churches. Thomas was recommended for ordination to the priesthood in May 1923, the records show. While living in Pineville, Thomas had a third child, a son, who reported the town as his place of birth in his 1943 draft registration card.

The Episcopal archives are expansive, but they don’t contain any record of Moore’s great-grandfather preaching for racial equality, any record of a conflict with the Ku Klux Klan, or any record that he said or did anything noteworthy during his brief stint with the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina between 1922 and 1924.

The archives served as the basis for A Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina, 1820-1957, a comprehensive, 900-page history book covering the diocese’s activities throughout those years at an excruciatingly granular level. Moore’s great-grandfather is only mentioned once in the book—in an index listing the names of every clergyman who worked in the diocese from 1820 to 1957. The book makes no mention of his sermons, the Klan, or any sort of white racial animus against the Church of the Redeemer in Pineville, where Moore’s great-grandfather worked. The most noteworthy accomplishment of the Pineville church, according to the book, was the hiring of a trained nurse in 1924 who engaged in “extensive work through the following years with the county physician” to take care of the sick.

A temporary tragedy did strike the Church of the Redeemer shortly after Moore’s great-grandfather departed in late 1924, but it had nothing to do with the Klan. The church’s medical work for the black community “suffered a great loss in the burning of the school house at Redeemer, Pineville, March 26, 1926,” the book reported. “However, a better one was soon erected.”