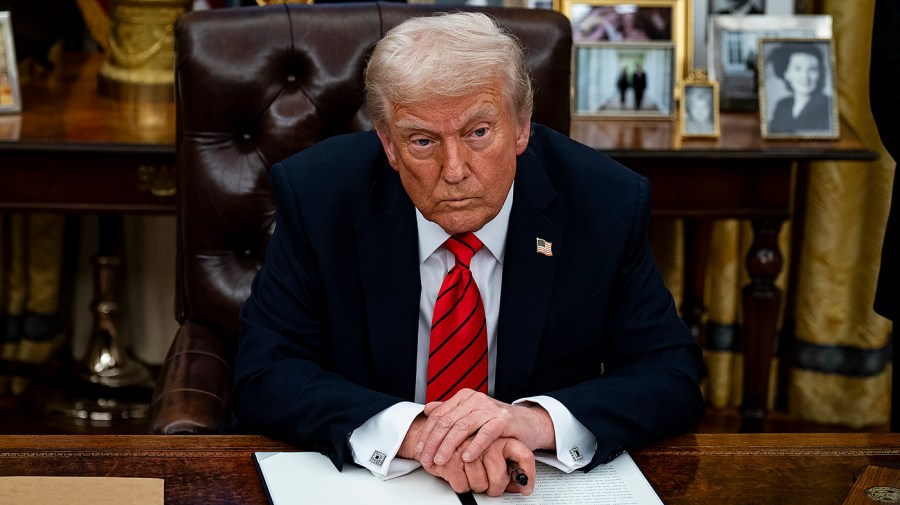

President Trump’s flood-the-zone strategy in the first month of his new presidency is catching the typically sluggish judiciary flat-footed.

More than 50 lawsuits challenging major administration actions have been filed at breakneck speed, leading to whirlwind showdowns in courtrooms across the country that has created challenges for both sides in the legal debate.

Justice Department lawyers have walked back statements hastily made in court. Challengers have scrambled to gather all the plaintiffs. And judges have tried to toe the line between acting fast and acting right.

“It’s hard for me to keep up. I don’t know whether you have been able to keep up,” said U.S. District Judge John Bates at a Monday hearing about online health data scrubbed by the Trump administration.

Trump has signed dozens of executive actions since returning to the White House, issuing directives upending policy across the board from immigration to gender to federal employee protections.

As legal challenges pour in, plaintiffs have sought swift relief. Judges have frequently set weekend deadlines and scheduled emergency hearings within hours of initial requests to temporarily block the actions.

“I know it didn’t make your weekends relaxed. It didn’t make mine relaxed either,” joked Bates, an appointee of the younger former President Bush, at Monday’s hearing.

“And I suppose you can ultimately point the finger to whoever you want, toward those who brought the lawsuit or those who were responsible for the conduct,” he continued.

The hastily scheduled proceedings at times have left lawyers unprepared, with multiple hearings being pushed into recess so government attorneys could touch base with the relevant agency personnel.

During a hearing last week in Washington, D.C., Justice Department lawyers struggled to reach an agreement with FBI agents who worked on Jan. 6 cases and sought to keep their names from being publicly released.

The FBI agents’ lawyers insisted any order must block all government entities — not just DOJ — from publishing the information but were met with resistance from DOJ.

“What is the hesitation?” pressed U.S. District Judge Jia Cobb, a former President Biden appointee.

“The government is a vast entity,” DOJ lawyer Jeremy Simon explained, suggesting such an affirmation would require a go-ahead from every agency in the government. “I’ve had this case for less than 24 hours.”

The hearing dragged on for roughly six hours, as government lawyers made intermittent attempts to reach “decisionmakers” within their agency to finally strike a deal. An agreement wasn’t reached until the next day.

A similar dynamic played out when a group of unions sued over Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency’s (DOGE) plans to gain access to Labor Department systems. After taking the bench for the first hearing, the judge encouraged the parties to see if they could find agreement.

The judge wasn’t called back for over an hour. When he returned, government attorneys indicated the negotiations included conversations with Labor Department officials, but it did not end in a deal. The hearing then continued, and the judge ultimately sided with the government.

Even after hearings, the Justice Department has caught mistakes made in haste.

Government lawyers corrected representations made to judges discovered after having “the benefit of more time to investigate the facts over the weekend” in at least two lawsuits.

In a case involving the DOGE team’s access to critical Treasury Department payment systems, DOJ lawyer Bradley Humphreys told a judge that the government had provided the wrong designation for a DOGE-adjacent employee.

Christopher Edelman, who represents the government in a challenge to its plan to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), said DOJ wrongly told the judge that just 500 employees had been placed on administrative leave, when it was actually more than 2,000 employees. He also said the government’s representation that only future contract obligations were paused was incorrect.

It’s not only the administration struggling to keep pace.

When Democratic state attorneys general organized last week to sue over DOGE’s access to the Treasury Department’s payment systems, they couldn’t agree in their announcements on who was part of the coalition.

One office claimed 12 states would sue. Another said the number was 14. When the suit was ultimately filed the next day, 19 total states had signed on.

Judges, too, have run into trouble. They’ve repeatedly been asked to clarify emergency rulings that included vague, sweeping language.

In a separate case challenging DOGE’s Treasury access, a judge early Saturday imposed far-reaching restrictions before the government could respond, a move met with swift condemnation from Trump and his allies.

Both sides agreed the order should be modified so that contractors who maintain the systems could resume access. A different judge on Tuesday retooled the earlier ruling accordingly but declined the Trump administration’s request to dissolve the restrictions entirely.

As plaintiffs press for swift relief, other judges have declined to rule so quickly — and chafed at suggestions otherwise.

“I’ll do what I can when I can,” Bates said at the DOGE-Labor hearing last week, which he also oversaw. “I’m not ruling on it sitting up here right now. You’ll have to wait and see when I get it out, and what it says, I will try to be as conscientious as I can, given the fact that it’s now a quarter of six on Friday afternoon.”

“It is what it is,” the judge said.