The laws of economics can be frustratingly inconvenient, especially in Washington. To many lawmakers, the fundamental principles of economics are neither fundamental nor even principles: They are tools to be bent, warped, and manipulated or outright ignored in order to yield up the answers those lawmakers want.

So it is that Democrats love to argue that raising taxes on things automatically yields more tax revenue for the government. They would have you believe that if you bought ten Big Macs at a cost of $5 each, you would also buy ten if the price were $7.50 after a tax increase. Economics teaches us that people just don’t act like that — it’s called elasticity of demand — even if lawmakers don’t understand.

Another example: By ignoring economic principles, the Congressional Budget Office — supposedly full of people who have at least studied economics — misjudged the number of people who would sign up for Medicaid under ObamaCare by at least 130 percent. It turns out that people really like free stuff.

Sadly, Republicans can be just as unwilling to acknowledge the same basic, fundamental principles as their left-leaning colleagues.

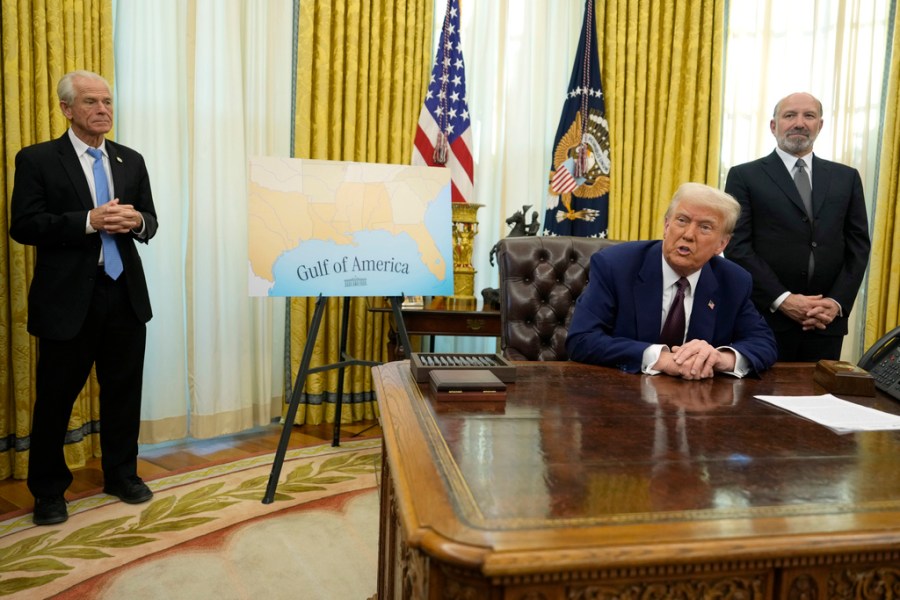

Thus it was this last week, when White House Senior Counsellor for Trade and Manufacturing, Peter Navarro declared that the upcoming basket of Trump Tariffs would raise $6 trillion in revenue in the next ten years, or an average of $600 billion per year.

Some basic math would suggest that, in theory at least, that is possible. Last year, Americans imported around $3.3 trillion worth of stuff from other countries. In order to raise that $600 billion a year, the tariff rate would have to be, on average across everything we import, about 18 percent. President Trump has dangled the prospect of tariffs ranging from 10 percent to 25 percent (or more, when it comes to China), so that 18 percent blended average at least isn’t outrageous, assuming that it covers literally everything, which even the White House hasn’t proposed … yet.

So the math could work, in theory. But economics is more than just math. It also considers human behavior. And one of the basic principles of economics is that of substitution. If the price of something goes up, people will try to find a similar good — a substitute — at a lower price.

It’s part of the same thing that makes the Democrats so wrong about taxes on Big Macs. Some people are going to adjust by going to KFC instead.

Don’t get me wrong: Substitution when it comes to tariffs isn’t a bad thing. Indeed, it is a principle that lies at the heart of the Trump tariff policy. He wants people to substitute American goods for the foreign goods that would be more expensive with tariffs added. He admitted that much this weekend when he said he was fully expecting the price of foreign-made automobiles to go up, which would, in turn, encourage people to buy more American automobiles.

That’s the idea behind the tariffs.

And frankly, I support the idea of bringing back American manufacturing. I live in South Carolina. I have seen what so-called “free trade deals” such as NAFTA — really misnomers for “negotiated trade deals that pick winners and losers” — did to the textile industry. More importantly, I have seen what those trade deals did to our communities and our families. Yes, we got slightly cheaper underwear and bedsheets, but entire swaths of our population got kicked out of the middle class.

Trump wants to fix that. One way to do that is through exactly the form of product substitution that tariffs would encourage. Faced with more expensive foreign-made goods, people will choose to buy American-made products, which in turn drives more American manufacturing.

However, to think the tariffs are going to do that but also raise $600 billion a year at the same time is absurd. In order for Navarro’s number to be accurate — that an 18 percent average tariff will raise $600 billion — American consumers would have to avoid substitution, instead buying foreign goods at tariff-elevated prices.

Indeed, for his revenue projections to be accurate, Navarro needs Americans to continue to buy as much stuff from overseas as they do today. Put another way, Navarro’s math assumes that the Trump tariffs create absolutely zero American jobs.

Or, you could look at it from the other side of the coin. If the Trump policies do what Trump wants them to do, and consumers start buying American goods instead of imports, then the tariffs would raise very little if anything. None of that should be that hard to grasp.

While not technically a formal principle of economics, there is a concept here with which everyone should be familiar: You cannot have it both ways.

Trump has strong political, philosophical, economic and even cultural reasons for taking a hard line on tariffs. He doesn’t need people coming out to defend them by using fuzzy math that every college freshman in Econ 101 can spot as political rather than economic.

Mick Mulvaney, a former congressman from South Carolina, is a contributor to NewsNation. He served as director of the Office of Management and Budget, acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and White House chief of staff under President Donald Trump.