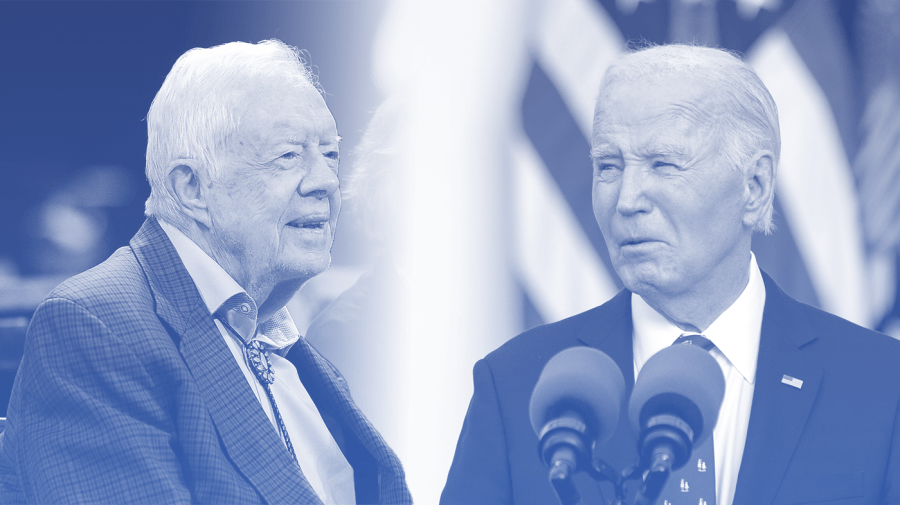

President Biden paid tribute to former President Carter soon after the 39th president’s death was announced Sunday.

But Biden could have been forgiven for some unease, given that Carter’s story offers plenty of uncomfortable comparisons with his own.

Speaking at a hastily arranged news conference in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where he is vacationing, Biden praised Carter, who died aged 100, as “a remarkable leader” and “a statesman and humanitarian.”

But most Americans did not see Carter that way during his time in the White House. And they do not appear to feel that way about Biden now.

The specificity of the parallels is striking.

Biden and Carter were both wounded politically by very high inflation. The damage they incurred on that topic was central to their departure from office after just one term.

Both were mired in low approval ratings.

Biden’s most recent Gallup approval rating, earlier this month, was 39 percent. In December 1980, as Carter prepared to leave office, 34 percent of Americans approved of his performance, according to Gallup.

In addition to the stench of failure that clings to all one-term presidents, both Carter and Biden experienced the further indignity of being succeeded by a Republican who was more dramatic, and more divisive, than themselves — and who had been widely mocked as unelectable by other Democrats and wide swathes of the media.

Former President Reagan is now so elevated in the Republican pantheon that it is easy to forget how he was derided at one point as a right-wing, lightweight former actor. He trounced Carter in 1980 regardless, with the Democratic incumbent carrying only six states and the District of Columbia.

Biden ran in 2020 to save “the soul of America” from a second term of then-President Trump. Four years later, he was pushed aside by his own party after a disastrous debate performance against his nemesis — and then saw Trump become the only president other than Grover Cleveland to be elected to nonconsecutive terms.

There is an additional problem for Biden, too. Carter enjoyed a rehabilitation of sorts because of his years of work after leaving the White House.

The Carter Center — founded by the former president and his wife Rosalynn in 1982 — won plaudits for activities ranging from public health initiatives in the developing world to the monitoring of elections.

Carter’s humility — returning to live in his modest home in Plains, Ga., after his time in the White House, and personally helping construct homes for Habitat for Humanity — also won admiration even from those who disagreed with him ideologically.

Among progressives, Carter enjoyed a late-in-life status boost as he lambasted former President George W. Bush’s record, especially on the Iraq War, and inveighed against Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

For Biden, at 82, the harsh reality is that there are unlikely to be significant postpresidential achievements.

There are, to be sure, some more encouraging parallels.

Biden’s most ardent loyalists contend that he will be viewed more favorably by history than he is in the current moment. They cite his efforts on infrastructure, combatting climate change and marshaling a coalition to aid Ukraine after Russia’s invasion.

Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan recently told The Washington Post that Biden has governed with an eye to how his decisions will reverberate “in decades” rather than according to the quadrennial electoral cycle.

Such claims mirror the efforts by some voices sympathetic to Carter to revise the negative perceptions of his presidency.

The pro-Carter case leans into some real achievements like the 39th president’s key role in the Camp David Accords that marked a new era in relations between Israel and Egypt.

Carter, too, can claim credit for taking steps toward the use of renewable energy — even installing solar panels at the White House — and to bringing a greater level of diversity to the judiciary.

But overall such achievements look likely to be overshadowed by bigger issues — and by a sense that both Carter and Biden are presidents who never quite met their moment.

Carter was ultimately and definitively undone by the hostage crisis in Iran.

More than 50 Americans were held in captivity after the U.S. Embassy in Tehran was stormed. Carter was unable to free them, his most disastrous failure being a helicopter-led rescue mission that came to grief in the Iranian desert in April 1980. Eight American service members were killed. The hostages would not ultimately be released until the first hours of Reagan’s presidency.

For Biden, the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 — which reached its nadir when 13 American service members and more than 100 Afghan civilians were killed in a suicide bombing near Kabul’s airport — saw his approval ratings sink. They never fully recovered.

Later in his presidency, his backing for Israel’s assault on Gaza following the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, divided his party and outraged progressives.

No presidency is solely about substance. The role of commander in chief has a performative aspect, especially in the modern era.

Carter, who had offered himself as a modest, healing force after the Vietnam War and the gothic dramas of the Nixon presidency, came to be seen as lacking in natural authority.

His so-called malaise speech, in which he warned of a national “crisis of confidence,” played into that perception. But so too did his subdued, cardigan-wearing persona.

For Biden, more concrete worries hobbled him — his age, his often-meandering public remarks and his cognitive abilities.

A young Biden was the first senator to endorse Carter when the Georgian ran for president in 1976.

Now, at the sunset of his own political career, the similarities between the two men must strike uncomfortably close to home.

The Memo is a reported column by Niall Stanage.