When the autopsy is conducted, the time of death for independent oversight of government agencies will be noted as 7:48 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 24, 2025.

That was when 17 inspectors general — presidentially appointed and Senate confirmed — across the federal government were sacked from their positions in the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, Veterans Affairs and more than a dozen other agencies due to “changing priorities.”

Apart from questions about procedural legality, the dismissals sent a chilling message to federal inspectors general across government: The more than 45 years of bipartisan support for independent oversight — oversight that has demonstrably improved government services and saved billions of taxpayer dollars — may be coming to an end.

Inspectors general work inside federal agencies to improve government efficiency and effectiveness through audits, inspections and investigations. But in order to speak hard truths to leaders about agency shortcomings, they rely on their authorities under the Inspector General Act of 1978. That law grants them independence from their agency head, financial independence through a separate appropriation, access to all agency information and personnel and an ability to review any issue they choose. And, at least in the past, they relied on strong support from Congress.

The civilian inspector general concept was derived in part from the military, where an inspector general provided an independent review of troop readiness. Over the last four decades, the number of inspectors general expanded from the original 12 to 74, and they operate within agencies large and small as independent units to combat waste, fraud and abuse. Half the inspectors general, those in the Cabinet departments and larger agencies, are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, while the other half are appointed by agency heads. Apart from the first presidential transition in 1980 after passage of the Inspector General Act, inspectors general have been recognized as apolitical professionals who were not required to submit their resignations during changes in administrations.

I worked as an inspector general at two different agencies and as deputy inspector general at a third. Our offices relied on these statutory authorities to deliver unsolicited and at times unpopular findings — like when we reported that the cost for a mobile platform needed to launch NASA’s next-generation rocket, first estimated at less than $400 million, had ballooned to more than $1.2 billion. Bechtel, the prime contractor on the project, likely did not want to read about its project management failures in a public inspector general audit. Nor did NASA leadership.

But Congress needed this information to help it conduct effective oversight and pressure agency leaders to improve their management of the project. In the aftermath of the Trump administration’s widespread firings, however, inspectors general may be hesitant to issue unflattering findings about agency programs — a dynamic that cuts to the core of the job.

Which brings us back to the state of independent, evidence-based oversight of federal agencies. Since the January terminations, Congress has largely absented itself from the conversation about the role inspectors general play in reviewing government programs. This failure to meaningfully defend the oversight system that Congress itself created will redound to its detriment now and in the future. In the short term, inspectors general — unsure of congressional receptivity to critical findings — may be hesitant to undertake such oversight or, if they do, may temper their message from the full-throated way the facts would otherwise dictate.

In the longer term, the nation may have crossed a threshold to a new era in which every incoming administration replaces inspectors general with candidates of their choosing — a world in which each attorney general or secretary of the Treasury gets to hire his or her own inspector general.

But if the new litmus test is whether inspectors general embrace a particular administration’s governing philosophy or policy priorities, then we have lost a proven, professional and apolitical tool to inform Congress and the public about the effectiveness of their investments in federal government programs. And that is a great loss.

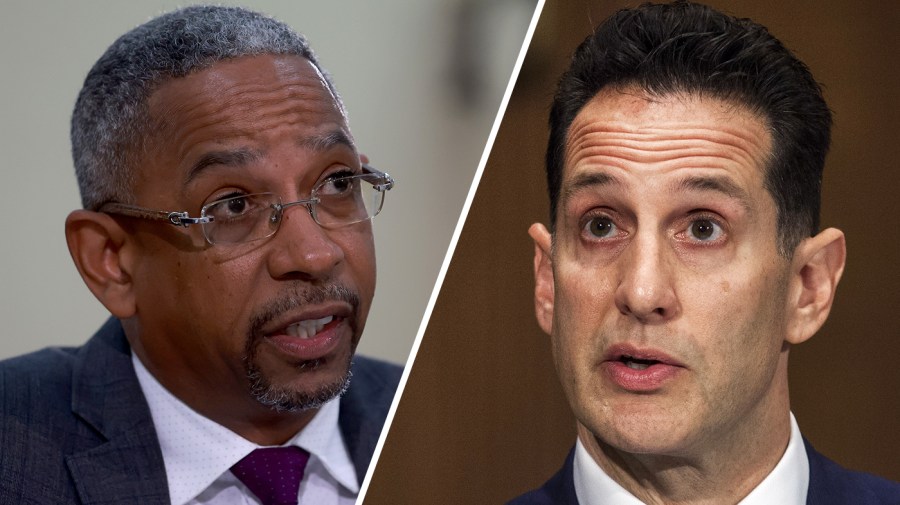

Paul K. Martin served for more than 25 years in the federal oversight community as inspector general at USAID and NASA and deputy inspector general at the Department of Justice. He was fired by email on Feb. 11, 2025.