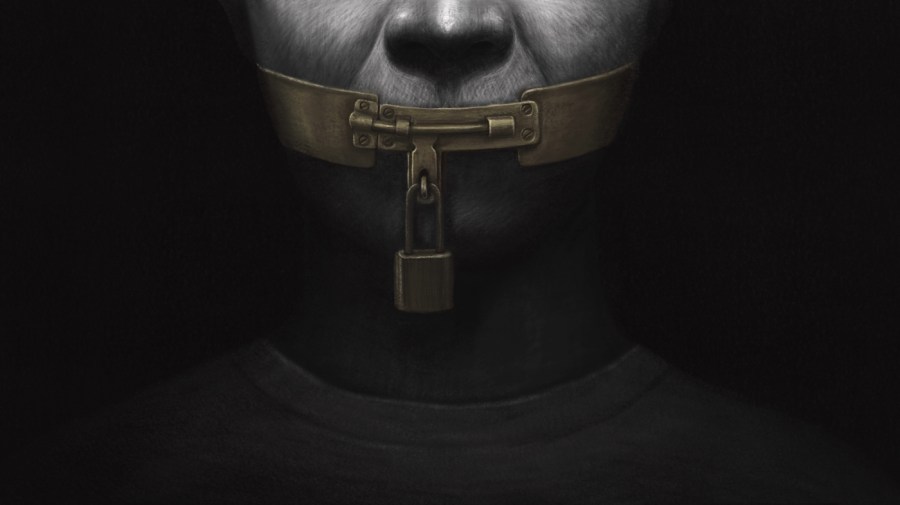

Much ink has been spilled about the growing regime of secrecy surrounding the death penalty in this country. In 2018, the Death Penalty Information Center reported that “During the past seven years, states have begun conducting executions with drugs and drug combinations that have never been tried before. They have done so behind an expanding veil of secrecy laws that shield the execution process from public scrutiny.”

“Since January 2011,” the organization noted, “legislatures in thirteen states have enacted new secrecy statutes that conceal vital information about the execution process. Of the seventeen states that have carried out 246 lethal-injection executions between January 1, 2011 and August 31, 2018, all withheld at least some information about the about the execution process.”

Since that report was written, the regime of secrecy has tightened its grip on what the public gets to know about executions. We were reminded of that last month when the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld a South Carolina policy that “prohibits the publication of interviews between prisoners and the media or members of the public.”

The court’s decision aided and abetted a cover-up of the conditions and treatment of South Carolina prisoners and death row inmates. It eviscerated the First Amendment guarantee of press freedom and undermined the public’s ability to make informed decisions about the state’s correctional policies.

The state’s policy governing “Employee and Inmate Relations With News Media” does more than conceal information about the conduct of executions in South Carolina. It also prohibits interviews with South Carolina inmates, including death row inmates, “by anyone,” and bans photography and video and audio recording of prisoners.

The American Civil Liberties Union of South Carolina notes that the state’s department of corrections “enforces the nation’s most restrictive policy on media access to prisoners,” taking the position that “[i]nmates lose the privilege of speaking to the news media when they enter” the state prison system.

The state explains its policy as “rooted in victims’ rights … The department believes that victims of crime should not have to see or hear the person who victimized them or their family member on the news.”

That explanation came last year after a prisoner, the notorious murderer Richard Murdaugh, gave an interview to Fox Nation. According to South Carolina’s Department of Corrections, Murdaugh “willingly and knowingly abused his telephone privileges to communicate with the news media for his own gain.”

The suit challenging the policy was filed by the ACLU of South Carolina in February 2024, although Murdaugh was not one of the inmates on whose behalf it was filed. It alleged that the policy infringed on the “First Amendment right to receive and publish the speech of incarcerated people … who seek to publish speech on several matters of deep public concern: prison administration, prison healthcare, gender equity, and the propriety of capital punishment.”

The policy suppresses “the speech of incarcerated people and plaintiff’s access to that speech” and “stifles the public’s access to information on matters of deep political concern.”

And South Carolina policy, the lawsuit adds, prohibits prisoners “from communicating with anyone who intends to publish prisoner speech, either in person, by video, or by telephone” and “does not allow incarcerated people to publish their own writings in media outlets.”

The two inmate plaintiffs in the lawsuit are Sofia Cano and Marion Bowman. Bowman is on South Carolina’s death row.

Cano is a transgender woman who wants to do an interview about the “propriety of transgender healthcare bans” in South Carolina prisons. Bowman wants to tell his story “to increase political pressure in favor of clemency (in his case), to shed light on the impropriety of capital punishment, and to inform the public about the inhumane treatment endured” in South Carolina’s prison system.

The Federal District Court that first considered the lawsuit dismissed it, ruling that there is “no First Amendment right to access prison inmates to conduct interviews for publication.”

On Dec. 13, the Fourth Circuit agreed. It cited a line of Supreme Court cases holding that “newsmen have no constitutional right of access to prisons or their inmates beyond that afforded the general public.”

The court rejected the contentions of the ACLU, stating that the precedents cited did not apply in this case because it already had access to the inmates and was already representing Bowman. It decided that the South Carolina policy did not stifle the public’s ability to obtain information about the treatment of prisoners or of those awaiting execution.

Here, the court made the arbitrary judgment that because inmates could write letters to or talk to lawyers who could in turn talk to the press, they did not need to give press interviews. This is the kind of judgment that should be left to the speaker and to the press, not made by a state with the blessings of a court.

The ACLU was right to note that the medium is the message.

As the organization argued, “A story about Marion Bowman — that is, a telling of his case and his life behind bars — is not functionally equivalent to a story by Marion Bowman. A blog post … about how great a loss it would be if South Carolina kills Marion Bowman is no substitute for the public hearing Marion’s own voice, his own laugh, his own anguish.”

“In the context of prison advocacy,” the ACLU correctly observed, “empathy is hard earned. The sound of another person’s voice can break the demonizing and otherizing constructs that the public has about ‘prisoners,’ and can reveal the multidimensional humanity possessed by those behind bars.”

That is true for anyone who is incarcerated, and it is especially true for death row inmates.

Moreover, every journalist knows that “A well-conducted interview can reveal hidden truths, challenge assumptions, and bring new perspectives to light, which can be both enlightening and transformative for the audience.” As an essay in National Geographic reminds us, “Some of the most important works of history are first person, from accounts by Frederick Douglass and Marie Curie to Charles Darwin and Anne Frank. They tell stories from places we haven’t been, experienced war and joy and exploration and discovery in ways we hadn’t seen, firing our imaginations and building our understanding.”

The Fourth Circuit has ensured that Sofia Cano and Marion Bowman will not have the chance to fire our imaginations and build our understanding by providing first-person accounts of their lives and experiences behind bars in South Carolina. The regime of secrecy has won another battle.

Cano, Bowman and all the rest of us are diminished because of the court’s decision.

Austin Sarat is the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science at Amherst College. His views do not necessarily reflect those of Amherst College.