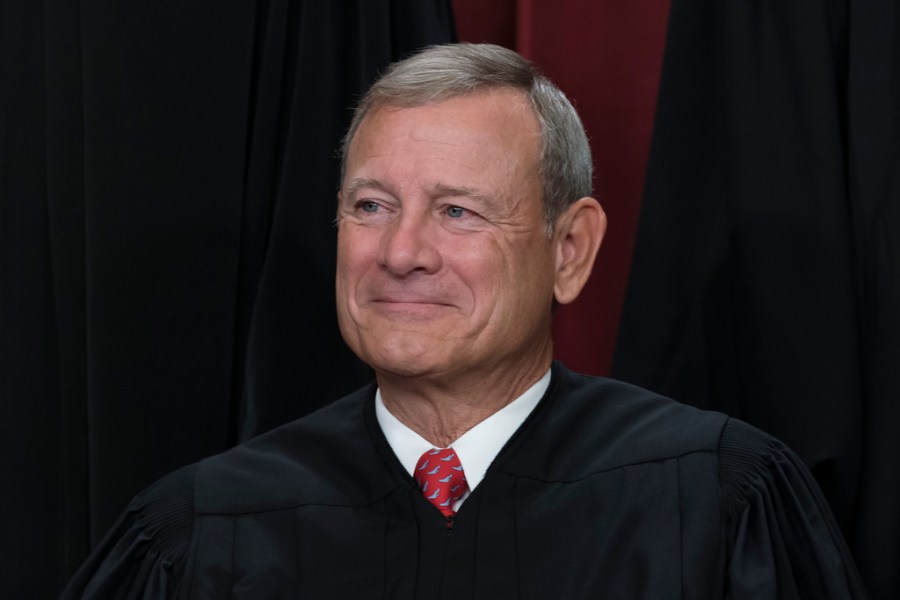

The Supreme Court is under great stress, if not in crisis. So says Chief Justice John Roberts in his annual report.

In important respects, Roberts is surely correct. The public’s trust in the court has slumped to catastrophic lows; individual justices are threatened with violence; the justices’ family privacy has been upended by demonstrations at their homes; the Internet is flooded with misinformation about the court and the justices that provokes deep concern about safety and reputation.

Roberts argues that members of the American public are responsible for the crisis. They threaten, they pry, they distribute misleading information. And he is correct, as far as he goes. The problem is that he does not go far enough.

The chief justice’s report stops far short of facing up to the many “self-inflicted wounds” that have contributed mightily to the current shameful circumstances.

During the last few years, the court trashed a woman’s right to shape her own personal destiny by declaring that there is no constitutional right to abortion. It protected gun rights with a religious vigor to thwart sensible state legislature’s efforts to protect school kids and the public.

After decades of judicial deference to the technical competence of federal administrative agencies, the court, in the name of bolstering democratic values, insisted that the judiciary — a politically unaccountable institution — would have the last word on the validity of federal agency rules. And it reached that conclusion some years after it thumbed its nose at the most politically accountable federal governing body — Congress — by invalidating part of the historic and seminal 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Only recently, the court granted the president unqualified immunity from criminal prosecution for so-called official acts. It thus rejected the profound concerns of the framers, who worried that the abuses of European monarchs might infiltrate the newly established office of the American presidency.

As devasting as these substantive decisions have been to the court’s public standing, many other considerations have also undermined the court’s legitimacy.

First, the six current conservative justices employ “originalism,” an interpretative methodology that insists that constitutional words and phrases should be taken in the way they were understood 235 years ago, when the Constitution was adopted. That means that America today should be governed by what a current justice, who is not a trained historian, concludes was the public meaning of the constitution in 1789. That approach, used a century ago, was soundly dismissed ninety years ago by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes.

Today’s exponents of originalism invite cynicism because in some cases they utilize a more flexible construction of originalism — for example, in upholding a gun restriction. In still other cases, they do not use originalism at all, despite having expounded that it is the only justifiable approach.

All of that is enough to conclude that the devotees of originalism are only selectively loyal, promoting it so long as that interpretive methodology provides doctrinal ammunition for outcomes they endorse, but that they don’t hesitate to push the blessed methodology aside when it provides no doctrinal road map to the preferred predetermined outcome.

The current justices have also stomped upon understandable and plain-vanilla ethical concerns that undermine the public’s confidence that the court functions as a disinterested interpreter of the constitution. Justice Clarence Thomas’s conduct constitutes exhibit A. He has given the nation a substantial list of highly publicized ethical lapses for which he displays no embarrassment and offers no apology.

Although Justice Samuel Alito’s conduct constitutes a pale version of Thomas’s disregard of commonsense ethical standards, there is no doubt that his ethical lapses likewise constituted a gross violation of sensible ethical norms.

There is still another reason as to why the court’s public reputation has sunk into the mud. Five conservative members on the court today were confirmed with fewer than 60 Senate votes. This suggests that senators thought that the nominees’ extreme perspective threatened not just the court but also the nation.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh squeaked by with 50 votes for confirmation. Thomas and Justice Amy Coney Barrett each received only 52. Justice Neil Gorsuch was confirmed with 54 votes and Alito with 58 votes. These vote tallies are in sharp contrast, for example, to Justices John Paul Stevens (98 votes), Sandra Day O’Connor (99 votes), Antonin Scalia (98 votes), Anthony Kennedy (97 votes), David Souter (90 votes), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (96 votes) and Stephen Breyer (87 votes).

It isn’t just the slim confirmation margins that encouraged public distrust of the court. The nomination process for Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett wreaked with political pollution. Gorsuch became a nominee only after the Republican-controlled Senate refused to hold hearings on President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland. Kavanaugh was confirmed by a mere 50 votes after he was accused of sexual misconduct. And President Trump nominated Barrett within weeks of the 2020 presidential election, only to have the Republican-controlled Senate steamrolled her nomination to the finish line.

In worrying about the court and whether the American people will comply with its rulings, Roberts fails to acknowledge any of these highly relevant factors that damage the court’s public standing. He surely knows of them and their relevance, but he adopts an ostrich posture, with his head buried, and that too contributes to the court’s very condition that he bemoans in his annual report.

If Roberts wants to address the problems the court confronts, he should lift his head out of the sand, look in the mirror, and then act accordingly, starting with an actionable code of ethics.

David Rudenstine is professor at Cardozo School of Law.