The past three presidential inaugurations have set a dubious record: Each saw the oldest man in history sworn into America’s highest office.

In 2017, Donald Trump, aged 70, became the oldest president to begin a term, comfortably surpassed in 2021 by 78-year-old Joe Biden. And when Trump took the oath of office again last month, he was 159 days older than Biden was four years ago.

Biden’s age and cognitive condition were central elements of the early election campaign. They weighed so heavily that he was forced to withdraw from the race in July, clearing the path for Vice President Kamala Harris to take on Trump, who had attacked Biden relentlessly as “Sleepy Joe.”

The issue was given additional piquancy by the public deterioration of Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Cali.), elected to a fifth term in 2018 at age 85. Within two years, rumors of her cognitive decline and short-term memory loss were ubiquitous. In early 2023, Feinstein announced she would not seek reelection and then spent two months in the hospital with shingles. Her absence from the Senate Judiciary Committee delayed a number of confirmation hearings. When Feinstein returned, she was visibly frail and dependent on staff, and she died in September at the age of 90. There was a general feeling that her public decline was both damaging and undignified.

Meanwhile, there are serious anxieties about the lack of political engagement by younger voters. They often feel that mainstream politics neither represents nor serves them, and they consistently vote in smaller numbers than any other age group.

Younger politicians, more in tune with the concerns of voters of the same age cohort, have often been seen as a solution. When Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) won a House seat in 2018, she was at 29 the youngest woman ever elected to Congress, with star power and a potent platform.

While Trump is the oldest president ever sworn into office, 40-year-old Vice President JD Vance is the third-youngest to take on the role (after John Breckinridge, James Buchanan’s running mate, and Richard Nixon). Trump has also nominated relatively young candidates for major executive branch roles: Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth is 44; Tulsi Gabbard, the nominee for director of National Intelligence, is 43; and the presumptive ambassador to the United Nations is 40-year-old Elise Stefanik. The new White House Press Secretary, Karoline Leavitt, is 27.

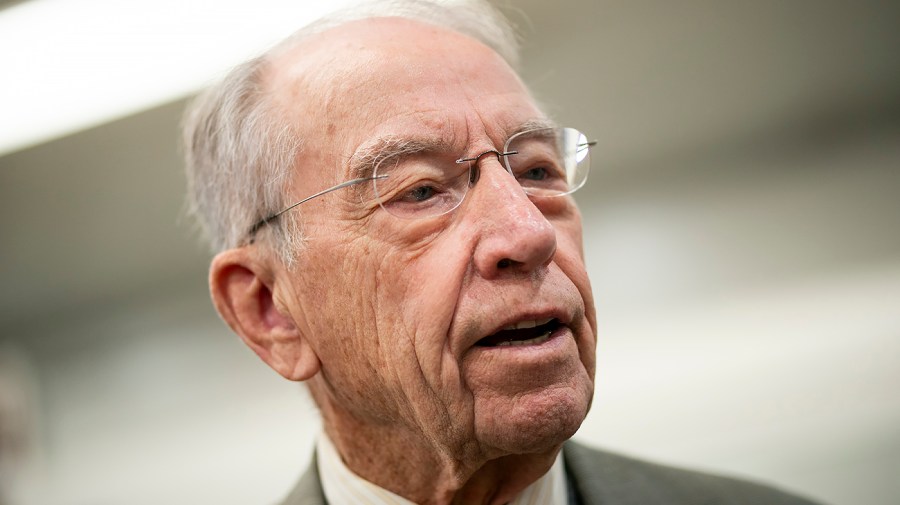

This leavening of youth stands out against a stubborn backdrop of gerontocrats. Senate Judiciary Chair Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) is 91. His colleague, Senate Foreign Relations Chair Jim Risch (R-Idaho) is 81. The ranking member of the latter committee, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), is 77. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) is 75 and his deputy, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), is 80.

In the executive branch, Linda McMahon, proposed as secretary of Education, is 76; Robert F. Kennedy Jr., nominee to run Health and Human Services, is 71; and Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum is 68.

This is partly a structural issue. The Senate relies heavily on seniority for leadership and committee assignments, an in-built bias towards older legislators. But choices are being made too: When House Democrats selected the ranking member of the Oversight Committee, Ocasio-Cortez lost out to Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), who will soon be 75.

The ideal polity would strike a balance between hard-won experience and youthful vigor. The lack of youth engagement in the political process is a serious matter. We cannot simply roll our eyes: it is hardly surprising that some younger voters feel little affinity with a system in which the third man in the presidential order of succession is Grassley, who was born the same year President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office.

Some favor term limits for members of the House and, especially, the Senate. This would certainly increase turnover; nine of the 100 senators have served more than 25 years.

Perhaps, though, that approaches the issue from the wrong end. While a few legislators and — one could argue — presidents outstay their welcome, the real problem is the dearth of younger leaders. Eighty-eight senators are over 50, while less than 10 percent of the House is under 40.

Effective and legitimate legislative and executive branches should reflect a sense of the nation they serve, without needing to replicate it exactly. Turnout among voters aged 18 to 24 rose sharply in the 2020 presidential election but fell back in 2024; it remains the lowest of the age cohorts and well below the national average.

Much has been made of the role of Barron Trump, the president’s 18-year-old son, in helping his father reach younger voters. He is said to have recommended Trump’s appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience, which has a strong following among young men. You do not need to wear a MAGA hat to see the value in thinking differently about communicating with potential voters.

If younger people are not visible in politics, it is less likely that younger voters will engage, and the reverse is true. Whether term limits or informal persuasion within the parties is necessary to ease politicians into retirement when the time comes is a matter of taste, but it can be part of a broader shift. A larger cohort of able younger legislators and officials will exercise their own pressure from below.

Politics should not feel like “Logan’s Run,” with men and women dispatched to the Carousel when they reach a certain age, but senescence cannot be the dominant feature either. If Vance moves to the Oval Office after Trump’s term, he would be the third-youngest president in history. Things can change quickly, but the next election is a long way away.

Eliot Wilson is a freelance writer on politics and international affairs and the co-founder of Pivot Point Group. He was senior official in the U.K. House of Commons from 2005 to 2016, including serving as a clerk of the Defence Committee and secretary of the U.K. delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.