In the wake of Democrats’ disappointing election losses, there is no shortage of theories and prescriptions. But the New York Times (“These Spiritual Democrats Urge Their Party to Take a Leap of Faith”) described one that warrants a respectful critique.

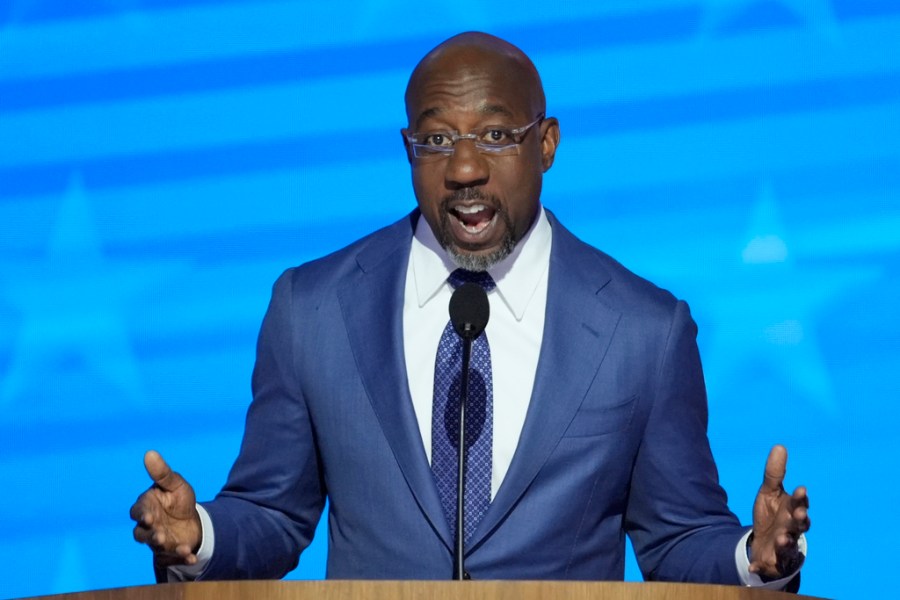

We greatly admire the Democratic leaders profiled by the Times. Rev. Raphael Warnock, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, Texas state Sen. James Talarico, Michigan state Sen. Mallory McMorrow and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg are good examples of devout politicians who connect with voters by explaining how their faith informs their values and their politics.

That does not mean, however, that religion is the only path to public service; or that more public religiosity is a good idea for every politician; or that every audience wants to hear faith talk from politicians.

We appreciate the nuance in McMorrow’s advice: talk about faith “if it is part of your experience in an authentic way.” She wisely identifies authenticity, not necessarily religion, as the key to building connections with voters.

For non-religious politicians, including dozens of members of Congress and countless officials and candidates at every level, leaning heavily on faith talk would be inauthentic if not disastrous. We have enough insincerity in politics, and voters are usually good at spotting fakes.

Moreover, many excellent politicians have minority faith views that diverge from the historically dominant paradigm — Christian, with some Jewish voices allowed — reflected in the Times profiles. Like the country itself, American politicians are becoming less of a Christian monolith. But prejudices and stigma persist. We question whether most voters would feel the same “connection” with politicians who regularly speak about their deeply held Humanism, nontheistic Buddhism, Muslim, Hindu or Sikh religious beliefs.

The voting public is changing too. Data shows Americans have been getting more religiously diverse, and much less religious overall, for several decades. The fastest growing religious category is unaffiliated. These so-called “nones” now represent one in three Americans making them the largest single religious group — bigger than Evangelicals and Catholics. While traditional religious denominations continue to shrink, “nones” have nearly doubled in just two decades. And with nearly half of Americans under 35 identifying as nonreligious, the electorate of the future will be even less religious.

Which makes public religiosity an unlikely panacea for Democrats’ electoral woes. Having too much politics at church is already driving people away from religion (20 percent of former believers cited this in a 2023 survey). It stands to reason that many voters would feel the same about having too much religion foisted on them by politicians.

Meanwhile, “nones” are emerging as one of the most important and reliable Democratic voting blocs. According to exit poll data from this year’s election, secular voters’ share of the Democratic coalition was 36 percent. In other words, more than one-in-three Harris-Walz voters were nonreligious, an increase from Biden’s 28 percent share in 2020. Democrats should take care not to alienate this fast-growing group.

Fortunately, there’s a way to connect withreligious voters and “nones.” New research from the Rural Voter Institute reveals that using moral language appeals to both groups. Thus, instead of leaning heavily on religious faith-talk and possibly alienating the growing secular base, Democrats can achieve broader appeal by just using values-based language.

And when Democrats do talk about personal faith, they should be as circumspect as Warnock. On “Meet the Press,” he made a strong statement in support of church-state separation and an important distinction: “It is the values that come from my faith that inform my work every day in D.C. and not the doctrine.”

He went on to use an inclusive phrase that nods at secular values held by nonbelievers: “moral courage.” The senator managed to express his Christian beliefs in a way that is personal to him, while taking care not to impose those beliefs on others and even to acknowledge us nonbelievers. These are best practices for every religious politician.

One aspect of religion Democrats should discuss a lot more is religious freedom — because Democrats have it right. At our best, we are interfaith and secular, respecting religious diversity and opposing any type of state religion, religious favoritism or imposition of religion on anyone who doesn’t want it.

We believe laws and public policies should be based on facts, science and shared values, not religious doctrines. And we vigorously defend the constitutional “wall of separation” between church and state — the most essential pillar of religious freedom.

Republicans, on the other hand, have it dangerously wrong. They seem to believe religious freedom applies only to their religion. They all but officially embrace Christian nationalism, routinely justify policy positions in Christian religious terms, and mock separation of church and state. This has galvanized evangelicals and conservative Catholics into a loyal GOP political base.

But surveys by the Brookings Institution and the Public Religion Research Institute show most Americans reject Christian nationalist ideas and 73 percent “prefer the U.S. to be a nation made up of people belonging to a wide variety of religions.” In a rapidly diversifying country that is becoming less religious, Republicans have made a dubious long-term bet. More fundamentally, in a secular republic founded on the bedrock constitutional prohibition against governmental establishment of religion, their position is antithetical to true religious freedom.

Surrendering the high ground on religious freedom would be a mistake for Democrats. Authentic personal expressions of how religious faith shapes one’s values are fine; but institutionalizing religion as the lens through which public policies are justified is problematic. It risks imbuing the party with religious authority, making it an arbiter of religion, and reinforcing the theocratic notion that our laws and policies should be based on religion.

Finally, before concluding that more public religiosity is good politics, we urge Democrats to consider recent Pew Research Center data. A large majority of voters (67 percent, including 54 percent of Trump voters) say being moral and having good values does not require belief in God. An even larger majority (71 percent overall, 56 percent of Trump voters) wants religion kept separate from government policies. It turns out even very devout people care about more than religion.

Democrats can appeal to people of faith — and many others — with policies like fair taxation, good health care, affordable housing and clean air and water. We need not engage in religious pandering to show that Democrats are moral, values-driven people who care about the wellbeing and quality of life of every American family.

Jared Huffman is a six-term congressman from California, co-chair of the Congressional Freethought Caucus, and the only openly Humanist member of Congress. Sarah Levin is co-founder and executive director of Secular Democrats America, and founder and principal at Secular Strategies.