In 2013, Brown University, where I am a professor of economics, invited New York City’s then-Police Commissioner Ray Kelly to give a lecture. Kelly had presided over a massive expansion of stop-and-frisk police tactics during his tenure, along with a host of other surveillance measures. At the time, I was a vociferous critic of America’s criminal-justice system and I was skeptical of stop-and-frisk. Under Kelly’s leadership, black New Yorkers were being stopped on the street and searched under the thinnest of pretexts. I had actually been detained by the NYPD in Harlem in 2010 while working as a visiting professor at Columbia, for the pretextual offense of “riding a bicycle on the sidewalk.”

Regardless of my feelings about his policies, I wanted to hear what Kelly had to say. He was an extremely powerful figure at the forefront of a controversial development in policing and I wanted to hear his justification for these tactics. There was plenty I wanted to say back to him, too. And I had a prime spot near the front of the stage to ask questions during the Q&A.

Kelly took the stage, but before he could get a word out, students in the audience began shouting him down. “Racism is not up for debate!” “No Justice! No Peace! No Racist Police!” “We’re asking you to stop frisking people!” The interruptions were met with scattered cheers. Marion Orr, the political-science professor who’d invited Kelly, asked the crowd to settle down and to wait for the Q&A, but the disruptions continued. After 15 minutes, it was clear that Kelly wouldn’t be allowed to speak, so he turned around and returned to New York.

I was stunned. I’d attended plenty of raucous, contentious lectures where members of the audience were clearly unhappy with the speaker. Hell, I’d even been the guy they were mad at! But whoever the speaker was, he needed to be heard out. Then, when the time came, whoever had the microphone could tell him just how wrong he was — and why. To shout down the speaker, to prevent him from presenting his argument, and to replace reasoned discourse with mob tactics was not what we did in the university.

I had always prized academia as a place where even unpopular thinking could be examined and debated without fear of repression. Even abominable ideas needed to be analyzed and subjected to examination rather than passed over in silence or repressed entirely. How else could we be sure that we could understand these ideas? How could we know they were so bad unless we engaged with them ourselves? The free exchange of ideas is one of the foundations of the modern university, indeed of modern democratic society. Without that exchange, it seemed doubtful that we could have either.

Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, immediately issued a statement condemning the protesters’ actions and reaffirming the university’s commitment to the free exchange of ideas. But when the university investigated the protesters, they were given a slap on the wrist and sent on their way. And worse, the university produced a navel-gazing report which concluded that, while the protesters should not have disrupted Kelly’s lecture, the university should have taken into consideration Kelly’s presence at Brown.

The commissioner, it seems, had the potential to “harm” students who had experienced trauma, possibly triggered by ideas like stop-and-frisk. In essence, the university was apologizing for doing exactly what it was supposed to do: expose its students to ideas and teach them how to formulate ideas of their own in response!

A precedent was set. At universities around the country, when a controversial, almost always conservative figure was invited to give a lecture, they could find themselves met by protesters who saw it as their mission to make sure the event never took place. Activists and some members of the media refer to these tactics with the rather genteel term deplatforming. A more honest term would be censorship.

In one sense, the students protesting Kelly’s appearance at Brown achieved their goal: he was silenced, and he left. But in another, more important sense, they missed the mark entirely: The reason for their protests — opposition to racially biased stop-and-frisk policing — was lost amid the controversy over their methods.

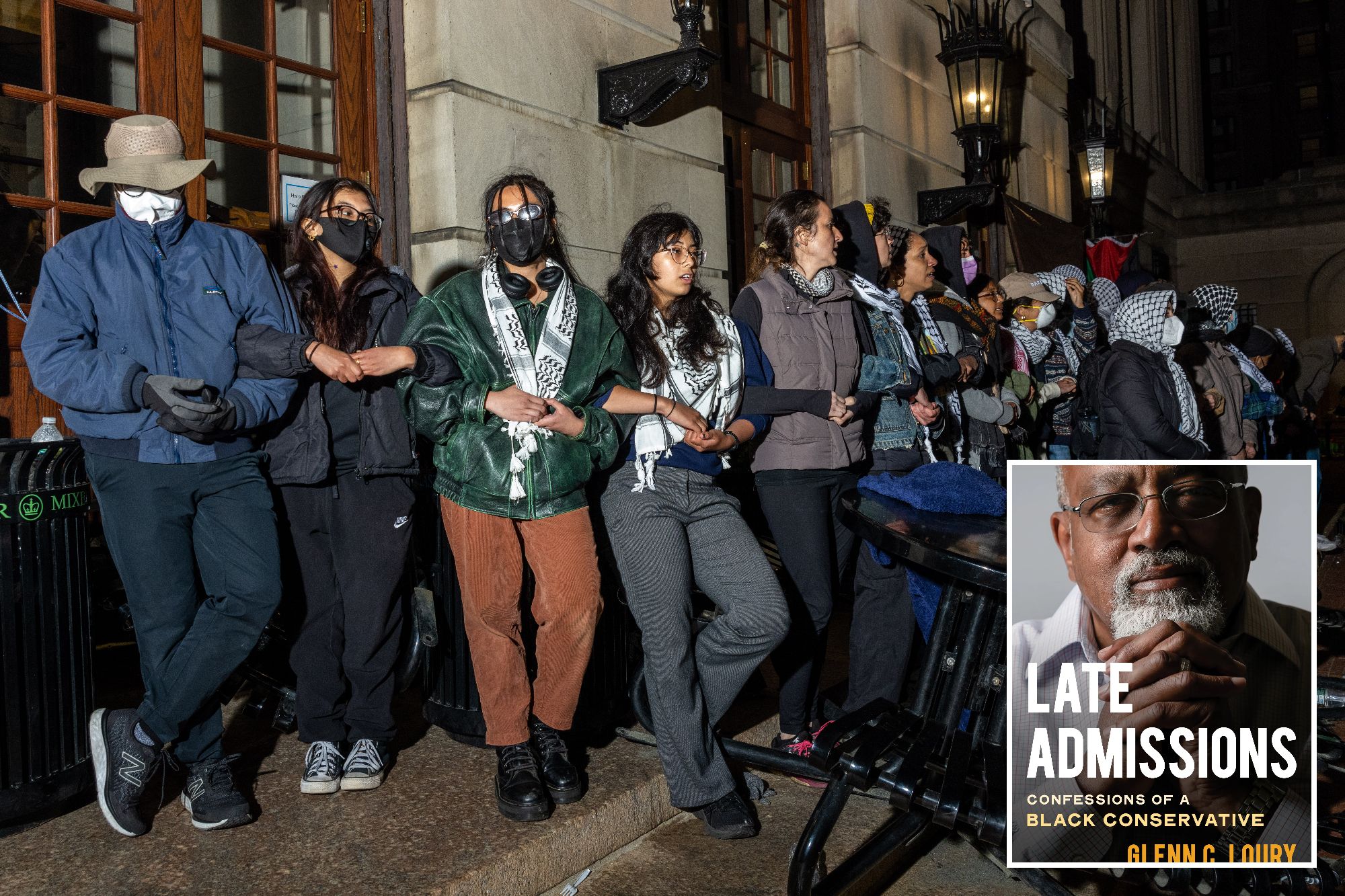

The same pattern repeats itself today in the pro-Palestine demonstrations on college campuses across the nation. There are many reasons to oppose Israel’s ongoing siege of Gaza and its dealings with the Palestinians. Yet the encampments and building occupations have once again turned the public’s attention to the protesters and their methods rather than the righteous cause the best of them represent.

If these students, like those who opposed stop-and-frisk in 2013, want to bring about change in the way America goes about its business, they need to get out of their own way. Otherwise, 10 years hence, the public may remember the tents and the arrests while struggling to recall what all that sound and fury signified. That would be a shame.

Glenn C. Loury is the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences and professor of economics at Brown University, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is the author of “Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative,” published by Norton next week, from which this essay is adapted.