In light of the extreme overuse of Adolf Hitler as a political epithet, we’ve already explored three other notorious 20th-century tyrants — Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong — whose cruelty and bloodlust qualify them as appropriate substitutes for the Nazi dictator in public discourse.

Though not referenced nearly as much as Hitler in ideological disputes, our three previous subjects do have significant name recognition among the general public.

So, here are some other despots whose crimes are often overlooked but who were no less brutal than their more infamous colleagues.

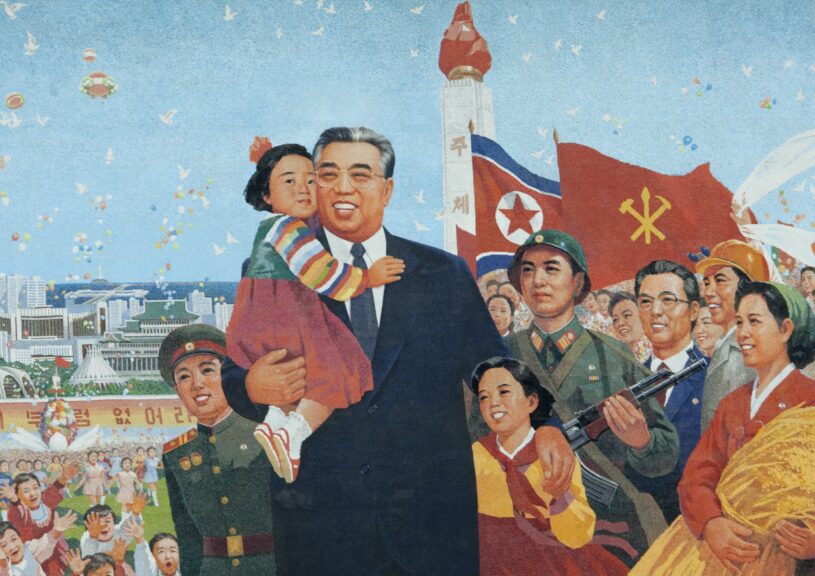

Kim Il-Sung

These days, Kim Il-Sung is best known as the father of Kim Jong-Il and the grandfather of North Korea’s current ruler, Kim Jong Un, but his 46-year rule laid the foundation for much of the suffering and depravity inflicted by his descendants.

Kim began his violent career as a guerrilla fighting against Japan, which had annexed Korea in 1910. He collaborated with the Chinese Communist Party in northern China during the 1930s and eventually became a major in an all-Korean battalion of the Soviet Red Army. After the Russians declared war on Japan in August 1945 and invaded Manchuria and Korea, they installed Kim as the leader of their new client state. He formally became the premier of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) in 1948.

Photo by Eric LAFFORGUE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Almost immediately, Kim began plotting a conquest of U.S.-aligned South Korea, launching a surprise attack in June 1950 and overwhelming the ill-prepared South Korean military.

While North Korea nearly succeeded in its goal of conquering the whole country, driving the South Koreans and a few American troops into a small pocket centered around the city of Busan, a counterattack by American forces sent Kim’s army reeling back over the border. The North had almost been completely conquered by the American-led U.N. forces when Mao Zedong decided to bail out Kim in October 1950, unleashing waves of Chinese troops to throw the Allies back into South Korea.

The frontlines eventually stabilized roughly along the original border, and the war dragged on for another 2 years. A ceasefire was finally signed in July 1953, but North and South Korea are still technically at war. Kim’s war of aggression caused the deaths of between 2.5 and 3 million people, many of them his own people.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE DAILYWIRE+ APP

After the war, he established the personality cult of the “Great Leader,” which was continued by his son and grandson. With an iron grip on the state’s media and education system, Kim Il-Sung elevated himself to near-divine status, creating one of the most repressive and totalitarian regimes ever seen in history. The country became isolated, resisting any outside influence in favor of Kim’s ideology of juche, “self-reliance.” The decades of incessant propaganda effectively brainwashed the North Korean population into becoming fanatically loyal to Kim. The entire society revolved around Kim Il-Sung — to question the Great Leader was to question reality itself.

The economic boom of the late 1950s and ’60s in the wake of industrialization gave way to an era of stagnation in the ’80s. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, coupled with economic mismanagement during the later part of Kim’s tenure, would lead to the food shortages that devastated the country during his son’s reign.

Kim died in 1994 from a heart condition, but his rule continues after death. A revised version of North Korea’s constitution issued in 1998 proclaims Kim Il-Sung the “eternal president” of North Korea.

Pol Pot

A military coup in Cambodia in 1970 triggered a civil war between the country’s new government and a communist guerrilla army, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot.

AFP via Getty Images

The U.S., embroiled in its own war in neighboring Vietnam, initiated a massive incursion into Cambodia later that same year to strike Viet Cong supply lines. The Khmer Rouge’s ranks swelled in response to the United States’ operations in the country and its support for the repressive military dictatorship. Once the U.S. stopped its bombing campaign in August 1973, the Khmer Rouge gained the upper hand, and communist troops entered the capital of Phnom Penh in 1975, ending a civil war that had claimed the lives of half a million Cambodians.

As the Khmer Rouge began to transform Cambodian society into a socialist utopia, Pol Pot’s obsession with communist purity quickly devolved into the insane. Private property, currency, and even religion were abolished. Anyone who wore glasses (since only intellectuals wore them, according to the Khmer Rouge), spoke a foreign language, or read novels could become a target of persecution under the new regime.

The Khmer Rouge set up compounds in cities that facilitated the torture and murder of hundreds of thousands of Cambodians deemed enemies of the state for being too educated or too prosperous. In one compound, known as S-21, only 12 out of nearly 17,000 prisoners survived.

Pol Pot believed that a purely rural, agrarian society would insulate the Cambodian people from the temptations of greedy capitalism and allow them to achieve true communism. He proclaimed that 1975 was “Year Zero” and ordered his troops to force hundreds of thousands of people to leave the cities to join communal farms and reeducation camps. Many died on the arduous journey to these camps.

People on the farms were placed in communal housing to de-emphasize the traditional family structure and were given only the basic necessities to survive. Formal education was suspended in 1977, and once children reached age 8 they were taken from their parents.

Workers on the farms endured grueling work conditions under the constant threat of beatings or execution by Khmer Rouge guards. Despite the effort to create an agrarian society, mismanagement of the communal farms caused widespread food shortages, causing even more deaths. The mass graves filled with those who died from starvation or were executed by the Khmer Rouge are known as the “killing fields.”

Photo by Alex Bowie/Getty Images

After several border skirmishes, communist Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia in December 1978, capturing Phnom Penh by January of the next year and ousting Pol Pot from power. He slunk back into the jungle to carry on a guerrilla war until his death in 1998.

It’s widely believed that around 2 million people, a quarter of the country’s population, died during Pol Pot’s 4-year reign.

Mengistu Haile Mariam

A coup in 1974 ousted Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and replaced him with a council dominated by communist military officers. Soon after, the vice chairman of the council, Mengistu Haile Mariam, orchestrated the assassination of the chairman and dozens of other officials to cement his position as the undisputed ruler of the country.

Photo credit should read AFP via Getty Images

After an assassination attempt on Mengistu by a rival communist group in 1977, he launched the “Ethiopian Red Terror” to purge his enemies from the country. Mengistu’s main quarry during the purge were rival Left-wing groups, but, like Pol Pot, he also targeted prosperous and educated Ethiopians. The torture and murder of political dissidents became a matter of course. Bodies were often left in the open as a warning to others, and family members were sometimes required to pay for the bullets that killed their loved ones in order to retrieve the body for burial. Estimates on the number of people killed during the 2 years of the Red Terror vary wildly, from at least 10,000 to over 700,000.

Human Rights Watch called the campaign “one of the most systematic uses of mass murder by the state ever witnessed in Africa.”

Throughout Mengistu’s tenure, Ethiopia was mired in conflicts with anti-government rebels as well as separatists in the regions of Eritrea and Tigray. Over 100,000 soldiers serving the government died during the 1980s due to the regional conflicts, while rebel and civilian deaths likely number in the hundreds of thousands. The war was marked by brutal reprisals on civilians from both government and rebel troops. Beheadings and mass strangulations were common methods of execution.

Ethiopia was able to successfully resist an invasion by Somalia in 1977, but the resulting crackdown on Somalis living in Ethiopia caused a refugee crisis that contributed to the instability that plagues Somalia to this day.

The war against the rebels, the forced collectivization of agriculture, and a drought led to a devastating famine in the mid-1980s. It affected nearly a quarter of the country’s population and ultimately killed over 1 million people. The suffering caused by the famine inspired a massive global humanitarian effort (the hit 1985 single “We Are The World” was produced to raise awareness of the famine) and even changed how aid organizations respond to such disasters.

The famine caused even more Ethiopians to join the rebels, and in 1991 they succeeded in overwhelming Mengistu’s forces and seized the capital.

After the fall of his government, Mengistu was given sanctuary in Zimbabwe by fellow dictator Robert Mugabe. In 2006, he was found guilty of genocide in absentia by an Ethiopian court and sentenced to life imprisonment — later changed to the death sentence — but extradition efforts have failed. He has lived in Zimbabwe’s capital since, outliving both Mugabe’s regime and Mugabe himself. Mengistu is currently 86-years-old.

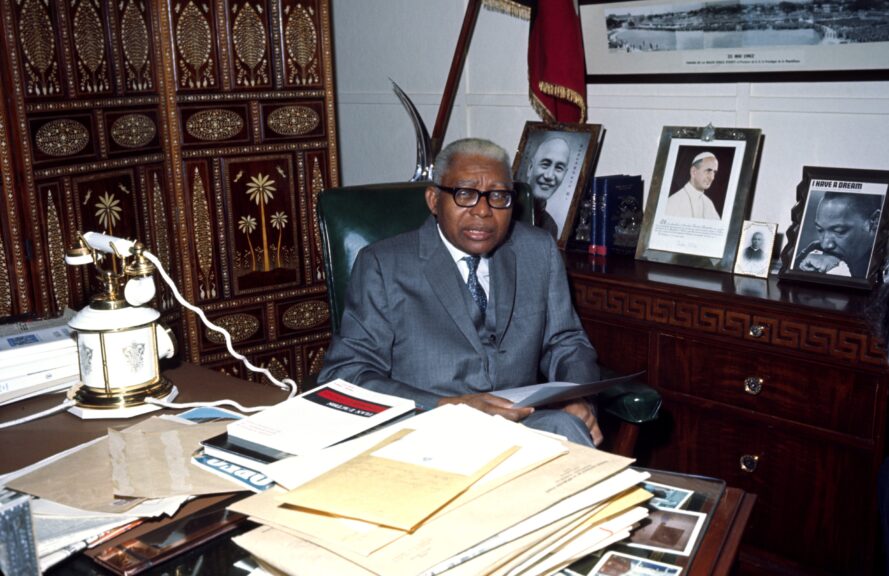

Francois Duvalier

If you’ve ever wondered why Haiti is such a Third World hellhole (especially given the fact it shares an island with the relatively prosperous Dominican Republic), Francois Duvalier deserves a significant amount of the blame.

(Original Caption) 3/18/1962-Port-Au-Prince, Haiti. An exclusive UPI interview, President Francoise Duvalier (shown in 1959 file photo). Getty Images.

After working as a doctor for nearly two decades, Duvalier entered politics and was elected president in 1957 by inflaming black Haitians’ resentment toward the mulatto elite. The arrests and disappearances of Duvalier’s political rivals followed. Over 300 people were killed and hundreds more were thrown in jail.

Duvalier’s enforcers in this initial purge would come to be known as the Tonton Macoute, named after a bogeyman from Haitian folklore. The Tonton Macoute quickly grew to double the size of the Haitian military and became the de facto government in the countryside. They arrested, terrorized, and tortured any potential opponents to Duvalier.

Corruption became endemic, with Duvalier’s officials and the Tonton Macoute regularly extorting regular Haitians. As a result, the economy deteriorated. By the end of his reign, 90% of the population was illiterate and the per capita income lagged far behind the rest of Latin America — $75 to $400.

In 1964, he rigged a constitutional referendum to become “president for life” and solidified his hold on the nation by engendering absolute terror in his citizens.

Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images

Duvalier studied voodoo, which was practiced by the vast majority of Haiti’s population, and spread rumors that he was a powerful sorcerer. He socialized with voodoo priests and participated in voodoo rituals. He also established a cult of personality around his supposed voodoo powers and promoted himself as the human embodiment of the nation.

The leader of the Tonton Macoute, Luckner Cambronne, grew rich off his own “industry” of selling Haitian corpses, often obtained through murder, to U.S. colleges and hospitals. He also sold massive amounts of blood extorted from Haitian citizens to American medical institutions. Duvalier’s henchmen would often stone victims or burn them alive, stringing up their corpses in public as a warning to other potential dissidents. The Tonton Macoute also cooperated with voodoo priests to fool the population into believing they possessed supernatural powers.

Duvalier died of heart disease in 1971, and he was succeeded by his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier. Jean-Claude continued his father’s repressive policies for another 15 years until he was overthrown in 1986. Up to 60,000 Haitians were killed between 1957 and 1971, but much like Kim Il-Sung, Duvalier’s inclusion on this list hinges not on his body count but on the sheer terror he was able to instill in his subjects.

In these smaller corners of the world, far away from the big headlines and the West’s public consciousness, these dictators were able to build totalitarian regimes just as brutal as those in Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, or Communist China. Their legacies continue to haunt the countries they ruled, and their impact on these unstable regions deserves more recognition.