It’s not just Claudine Gay. Harvard University’s chief diversity and inclusion officer, Sherri Ann Charleston, appears to have plagiarized extensively in her academic work, lifting large portions of text without quotation marks and even taking credit for a study done by another scholar—her own husband—according to a complaint filed with the university on Monday and a Washington Free Beacon analysis.

The complaint makes 40 allegations of plagiarism that span the entirety of Charleston’s thin publication record. In her 2009 dissertation, submitted to the University of Michigan, Charleston quotes or paraphrases nearly a dozen scholars without proper attribution, the complaint alleges. And in her sole peer-reviewed journal article—coauthored with her husband, LaVar Charleston, in 2014—the couple recycle much of a 2012 study published by LaVar Charleston, the deputy vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, framing the old material as new research.

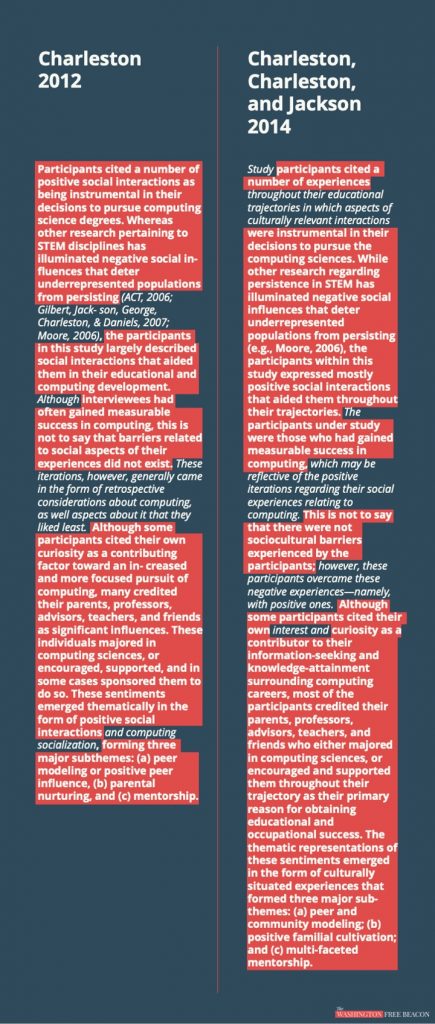

Through that sleight of hand, Sherri Ann Charleston effectively took credit for her husband’s work. The 2014 paper, which was also coauthored with Jerlando Jackson, now the dean of Michigan State University’s College of Education, and appeared in the Journal of Negro Education, has the same methods, findings, and description of survey subjects as the 2012 study, which involved interviews with black computer science students and was first published by the Journal of Diversity in Higher Education.

The two papers even report identical interview responses from those students. The overlap suggests that the authors did not conduct new interviews for the 2014 study but instead relied on LaVar Charleston’s interviews from 2012—a severe breach of research ethics, according to experts who reviewed the allegations.

“The 2014 paper appears to be entirely counterfeit,” said Peter Wood, the head of the National Association of Scholars and a former associate provost at Boston University, where he ran several academic integrity probes. “This is research fraud pure and simple.”

Sherri Ann Charleston was the chief affirmative action officer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison before she joined Harvard in August 2020 as its first-ever chief diversity officer. In that capacity, Charleston served on the staff advisory committee that helped guide the university’s presidential search process that resulted in the selection of former Harvard president Claudine Gay in December 2022, according to the Harvard Crimson.

A historian and attorney by training, Charleston has taught courses on gender studies at the University of Wisconsin, according to her Harvard bio, which describes her as “one of the nation’s leading experts in diversity.” The site says that her work involves “translating diversity and inclusion research into practice for students, staff, researchers, postdoctoral fellows and faculty of color.”

Experts who reviewed the allegations against Charleston said that they ranged from minor plagiarism to possible data fraud and warrant an investigation. Some also argued that Charleston had committed a more serious scholarly sin than Gay, Harvard’s former president, who resigned in January after she was accused of lifting long passages from other authors without proper attribution.

Papers that omit a few citations or quotation marks rarely receive more than a correction, experts said. But when scholars recycle large chunks of a previous study—especially its data or conclusions—without attribution, the duplicate paper is often retracted and can even violate copyright law.

That offense, known as duplicate publication, is typically a form of self-plagiarism in which authors republish old work in a bid to pad their résumés. Here, though, the duplicate paper added two new authors, Sherri Ann Charleston and Jerlando Jackson, who had no involvement in the original, letting them claim credit for the research and making them party to the con.

“Sherri Charleston appears to have used somebody else’s research without proper attribution,” said Steve McGuire, a former political theory professor at Villanova University, who reviewed both the 2012 and 2014 papers.

One-fifth of the 2014 paper, including two-thirds of its “findings” section, was published in the 2012 study, according to the complaint, and three interview responses are identical in both articles, suggesting they come from the same survey.

According to Lee Jussim, a social psychologist at Rutgers University, “it is essentially impossible for two different people in two different studies to produce the same quote.” At best, he said, the authors got their wires crossed and mixed up interviews from two separate surveys, both of which just happened to involve 37 participants with the exact same demographic profile. At worst, the authors committed data fraud by framing old survey responses as new ones—a separate and more serious offense.

The Journal of Negro Education did not respond to a request for comment. Sherri Ann Charleston, LaVar Charleston, and Jerlando Jackson did not respond to requests for comment.

Monday’s complaint, which was filed anonymously, comes as Harvard is facing questions about the integrity of its research affiliates and the ideology of its diversity bureaucrats, most of whom report to the sprawling office that Sherri Ann Charleston oversees.

The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, one of Harvard Medical School’s three teaching hospitals, announced in January that it would retract six papers and correct dozens more after some of its top executives were accused of data manipulation. That news came on the heels of a viral essay in which Carole Hooven, a Harvard biologist, described how she had been hounded out of a teaching role by her department’s diversity committee after she said in an interview that there are only two sexes.

The school is also facing an ongoing congressional probe over its handling of anti-Semitism and its response to the plagiarism allegations against Gay, which Harvard initially sought to suppress with legal saber-rattling. Half of Gay’s published work contained plagiarized material, ranging from single sentences to entire paragraphs, with some of the most severe lifts coming in her dissertation. Though Gay stepped down as president on January 2, she remains a tenured faculty member drawing a $900,000 annual salary.

Some of Charleston’s offenses are similar to Gay’s. In her 2009 dissertation, for example, Charleston borrows a sentence from Eric Arnesen’s 1991 book Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863-1923, without quotation marks and without citing Arnesen’s work in a footnote.

She also lifts full paragraphs from her thesis adviser, Rebecca Scott, while making minimal semantic tweaks.

“There’s simply not enough difference to consider them original words,” said Jonathan Bailey, the founder of the website Plagiarism Today. “Though the sources in those examples are cited”—Charleston includes a footnote to Scott at the end of each passage—”the text either needed to be quoted or properly paraphrased.”

Bailey added that the plagiarism of Scott alone merited an investigation—ideally, he said, “by a neutral party with no ties to either the school or the school’s critics.”

Harvard did not respond to a request for comment. Scott and Arnesen did not respond to requests for comment.

Charleston also lifted language from Louis Pérez, an historian at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; Alejandro de la Fuente, an historian at Harvard; and Ada Ferrer, an historian at New York University, among other scholars.

Charleston cites each source in a footnote but omits quotation marks around language copied verbatim. The omissions violate Harvard’s Guide to Using Sources, a document produced for incoming students, which states that quotation marks are required when “you copy language word for word.”

Pérez, de la Fuente, and Ferrer did not respond to requests for comment.

The range of examples presented in the complaint, which was also filed to the University of Michigan and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, highlights how plagiarism can shade into more severe forms of misconduct when it involves interviews or other data.

In fact, some experts said the term “plagiarism” didn’t quite capture the dishonesty of duplicate publication, which is sometimes categorized as a separate offense and accounts for 14 percent of all paper retractions in the life sciences.

“You cannot just republish an old paper as if it is a new paper,” Jussim, the Rutgers psychologist, said. “If you do, that is not exactly plagiarism; it’s more like fraud.”

Wood said the case was really a combination of the two offenses. “Because the second paper, on which Sherri Ann Charleston is one of the three co-authors, recycles so much of the text of the original paper by LaVar J. Charleston, this does have the earmarks of plagiarism, but the plagiarism is compounded by an even larger effort to deceive,” he said. “The universities and journals need to investigate.”

While scholars can reuse data across multiple papers, they must make clear when they are doing so and provide appropriate attribution to earlier studies, per guidelines from the Office of Research Integrity and the editorial policies of top academic journals, including Nature and Cell.

But the 2014 paper never indicates that it is reusing research from 2012. Instead, it claims to present new data that fill a “gap” in the literature and “corroborate” the 2012 study, among others, and on two occasions refers to survey subjects as “participants in this study.”

Those participants appear to be the same people whom LaVar Charleston interviewed in 2012. Both surveys involved the same number of undergraduates, graduate students, Ph.D.s, and students at historically black colleges—all drawn from the same computer science conference—a similarity that experts said was a red flag.

“It is curious that the proportions are identical,” said Debora Weber-Wulff, a German computer scientist who researches plagiarism and other forms of academic misconduct. “This would be grounds for the universities in question to request the data and investigate.”

Jussim agreed. “This seems sufficiently improbable that, absent something saying they are re-reporting an already-published study, it would be fraud,” he said.

LaVar Charleston did not respond to a request for comment about whether the two studies used the same interviews. The University of Michigan said it was “committed to fostering and upholding the highest ethical standards in research and scholarship,” but declined to comment on the complaint. The University of Wisconsin-Madison told the Free Beacon it had “initiated an assessment in response to the allegations.”

The main difference between the papers is a long section in the 2014 article about “culturally responsive pedagogy theory,” which the authors say their findings support. Both articles are littered with the tropes of progressive scholarship, including a disclaimer about “positionality”—the authors assure readers that they reflected on their own “racial, gender, and socioeconomic status”—and a lament that computer science is a “White male-dominated field.”

Both also criticize the idea that “computing sciences is for nerds, only for White people, [and] only for geniuses.”

Such language is typical of the diversity initiatives Charleston oversees. Since 2020, her office has pumped out a stream of materials that bemoan the “weaponization of whiteness,” discuss the ins and outs of “white fragility,” and urge students to “call out” their peers for “harmful words.” One message, signed by Charleston herself, was titled “A Call to Dismantle Intersecting Oppressions.”

“We must continue to work against systematic oppression in all its forms—racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and more,” she wrote.

Her office also curates resources for students seeking to become fluent in progressive patois, including a “glossary of diversity, inclusion and belonging (DIB) terms” that provides examples of “gaslighting.”

Tactics can include “shooting down the target’s ideas,” the entry reads—or “taking credit for them.”