It’s raining chem.

Toxic perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals,” have turned up in yet another remote corner of the environment: rainfall.

Chemical companies invented PFAS — a chemical class that’s expanded to include nearly 15,000 varieties — in the 1940s for its fire, water and grease-repellent properties, and used as an ingredient, coating or sealant for hundreds of materials and everyday goods, everything from paint to makeup to food packaging.

Yet health experts have only recently begun to explore the harmful — and potentially carcinogenic — properties of PFAS, which have been detected all over the world and at every level of the food chain.

Forever chemicals have already been found in drinking water and seafood — so researchers at Florida International University in Miami were not surprised to see it again in rainwater, per a Phys.org report.

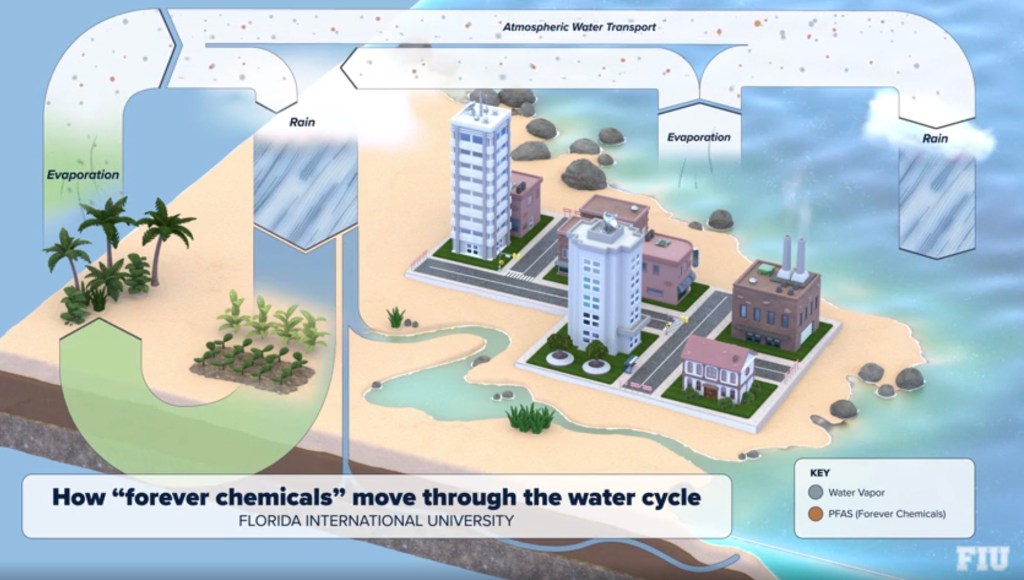

“PFAS are practically everywhere,” said FIU Assistant Professor of Chemistry and study author Natalia Soares Quinete. “Now we’re able to show the role air masses play in potentially bringing these pollutants to other places where they can impact surface water and groundwater.”

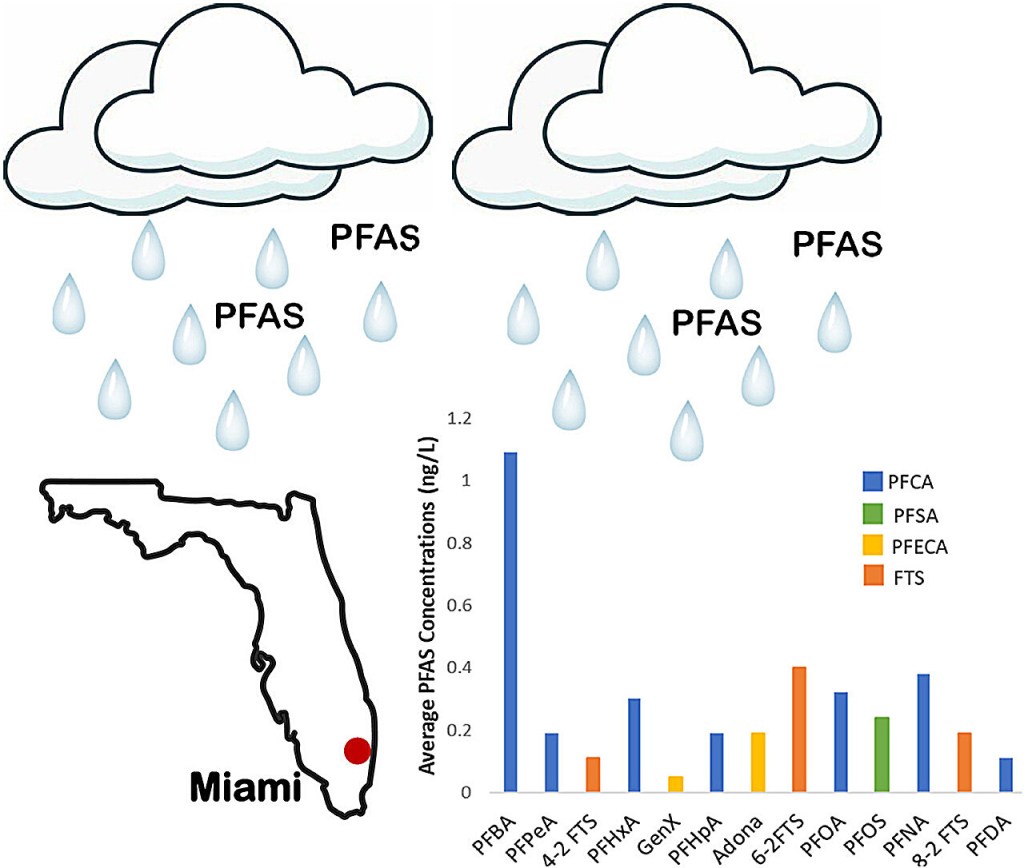

Quinete’s team found 21 types of PFAS, including two banned substances, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). The most frequently identified type, found in 74% of the samples taken between October 2021 and November 2022, were perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), which are usually seen in non-stick cookware, stain-resistant surfaces, food packaging and firefighting foams, to name a few sources.

Researchers can trace many of the substances back to a local source, while others had probably come from known manufacturers of PFAS-laden products up and down the East Coast, carried downwind via dust particles or evaporation.

Seasonal weather shifts, such as the Northeastern air masses that carry dry winds South during winter in North America, had likely encouraged these substances to accumulate throughout the Miami region, indicated by variable concentrations of specific PFAS throughout the testing period.

“The season variations were interesting to us,” said Maria Guerra de Navarro, a graduate student who assisted with the new study, published in Atmospheric Pollution Research. “We know there are northern states with manufacturing that matches back to the PFAS we saw, so it’s likely that’s where they are coming from.”

FIU researchers previously warned about PFAS they found in South Florida’s Biscayne Bay, home of threatened sea life such as dolphins and manatees.

The Emerging Contaminants of Concern lab in FIU’s Institute of Environment continues to expand on their understanding of how PFAS travel through the environment by investigating how many PFAS can be packed onto nanoparticles that measure seven times smaller than a strand of human hair.

Said Guerra de Navarro, “This is all about creating awareness that this is all one world. What’s happens in one area can impact here, there, everywhere. We have to be thinking about how to prevent these chemicals from going all over the world.”