With Republicans securing control of the House, Senate and White House in the election, they are poised to claw back major legislation Democrats have passed to fight climate change.

Chief in the GOP’s crosshairs are provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act — a massive climate, tax and health care package that contains hundreds of billions of dollars worth of tax credits for renewable energy, electric vehicles, domestic manufacturing, nuclear power, biofuels and more and was projected to deliver serious reductions in planet-warming emissions.

While a handful of Republicans have indicated they don’t want to eliminate all the law’s incentives for low-carbon energy, some, like subsidies for electric vehicles, could be on the chopping block.

“I think there are some of them that should go away: the tax credits for purchasing of electric vehicles, especially up to $500,000 in income, the tax credits for charging stations,” Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R-Iowa), chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus, told The Hill.

President-elect Trump was noncommittal on the campaign trail about whether he wanted to repeal this particular credit, but Reuters reported Thursday that the Trump transition team wants to axe it.

Other provisions of the law, which passed without a single GOP vote, are also likely to be repealed under the coming Republican trifecta.

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), who is poised to become the chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, said in a statement this week that Republicans would move quickly to repeal a program that charges oil and gas producers if they have high levels of methane emissions.

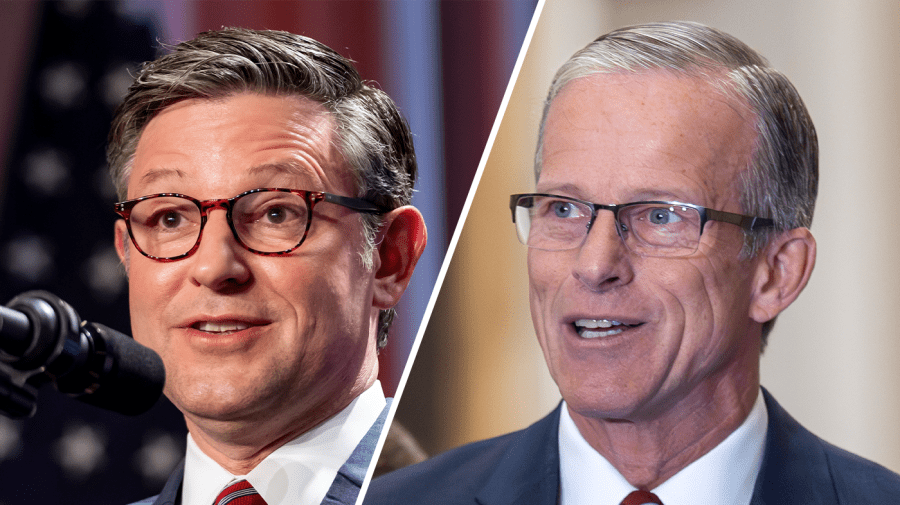

Meanwhile, Rep. Brett Guthrie (R-Ky.), who is in the running to lead the House Energy and Commerce Committee next year, told The Hill that Republicans would probe investments made under $27 billion “green bank” provisions of the law that seek to fund projects that mitigate climate change or otherwise reduce pollution.

“If there’s any money left we need to stop it from going out and we need to have oversight of what went out,” he said.

Over the summer, Speaker Mike Johnson’s (R-La.) office likewise singled out the law for cuts, including “repeal wasteful Green New Deal tax credits” in a plan for the first 100 days of then-candidate Trump’s second term.

Trump himself has called for a repeal of “insane wind subsidies” — though it’s unclear what such a repeal would look like, as the law allocates no money specifically for wind and instead is written so that incentives accommodate any type of energy whose planet-warming emissions are below a certain threshold.

Even some Republican allies expressed concern in the wake of the election that a wide array of these incentives could disappear.

“Overall, those tax credits, whether it’s 45X or 45Q or 45V and the tech neutral … type of tax credits, I think are all under threat,” said Heather Reams, president of Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, referring to credits for domestic manufacturing, carbon capture and hydrogen energy, respectively.

The extent of potential cutbacks is the subject of debate within the party. In August, a group of 18 Republicans wrote to Johnson asking him not to repeal all of the tax credits.

“Prematurely repealing energy tax credits, particularly those which were used to justify investments that already broke ground, would undermine private investments and stop development that is already ongoing.” they said in the letter.

“There needs to be a conversation with members about the energy credits in the Inflation Reduction Act,” said Miller-Meeks, one of the letter’s signatories.

Johnson indicated in September the GOP could leave some of the tax credits intact, saying “you’ve got to use a scalpel and not a sledgehammer, because there’s a few provisions in there that have helped overall.”

The question of which of the incentives should be preserved may also be the subject of some internal division, however.

While Miller-Meeks wants to cut electric vehicle subsidies, Rep. Buddy Carter (R-Ga.), whose district is home to a major electric vehicle and battery manufacturing plant, was less committed when asked about that particular tax credit this week.

“That’s just something we’ve got to look at,” he told reporters.

Rep. John Curtis (R-Utah), who will move over to the Senate next year, acknowledged the electric vehicle tax credit is one his party dislikes, saying “EV is one I think that typically gets beat up on.”

Speaking with reporters Thursday, he didn’t directly say whether he’d want to repeal the incentive, but he did say he thinks lawmakers should try to assess whether it’s meeting its objectives.

Asked about the technology neutral credits for low-carbon energy, Curtis also didn’t say whether he supported eliminating or capping them, but he pointed to his concerns about the national debt, saying “we’re spending too much money.”

The law’s tax credits have spurred significant investments in a wide range of climate-friendly technologies since its passage in 2022 — the majority of which have gone toward projects in Republican-held districts, the American Clean Power Association said last year.

Analysts with BloombergNEF told The Hill this week that repealing them would have an impact on future buildout and climate change, but that the low-carbon energy sector would not be completely wiped out.

“If they were repealed, for projects beginning construction in 2026 or later, we would see about a 17% drop in wind, solar and storage build collectively, concentrated, especially in wind and especially in offshore wind,” said Derrick Flakoll, a policy associate at Bloomberg.

Meredith Annex, who heads the firm’s clean power research, said that a repeal would likely cause a delay rather than less adoption of renewables in the long term — but such a delay could worsen climate change.

She said that if the world is trying to limit warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, which could help avoid certain climate “tipping points” that are difficult to reverse, “any delay makes that modeling even harder to achieve.”

Zack Budryk contributed.