On Friday, May 31, alumni descended on Columbia University’s Manhattan campus to celebrate their class reunions. In addition to eating and drinking, the festivities included several panel discussions featuring professors and administrators.

One, focused on Jewish life on campus, was particularly newsworthy. Student protesters who had broken into and occupied a university building during the academic year had reconstituted themselves to disrupt reunion festivities, and, as the protesters were preparing to erect a new encampment, the university held a panel discussion about the past, present, and future of Jewish life at Columbia.

The event featured the former dean of Columbia Law School, David Schizer, who co-chaired the university’s task force on anti-Semitism; the executive director of Columbia’s Kraft Center for Jewish Life, Brian Cohen; the school’s dean of religious life, Ian Rottenberg; and a rising Columbia junior, Rebecca Massel, who covered the campus protests for the student newspaper.

In the audience, according to two attendees, were several top members of the Columbia administration. Given the sensitivity of the subject—the eruption of anti-Semitism on campus in the wake of Hamas’s Oct. 7 terrorist attack on Israel put a national spotlight on the school, and Columbia recently settled a lawsuit with a Jewish student who accused the school of fostering an unsafe learning environment—the administrators’ presence made sense.

The administrators included Josef Sorett, the dean of Columbia College; Susan Chang-Kim, the vice dean and chief administrative officer of Columbia College; Cristen Kromm, the dean of undergraduate student life; and Matthew Patashnick, the associate dean for student and family support.

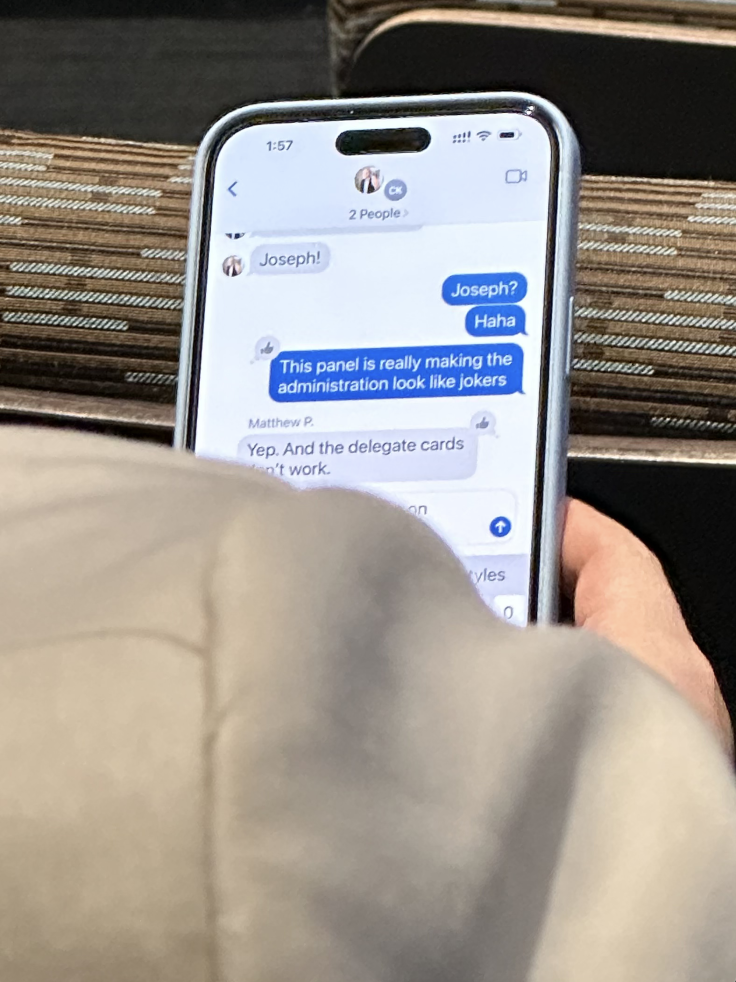

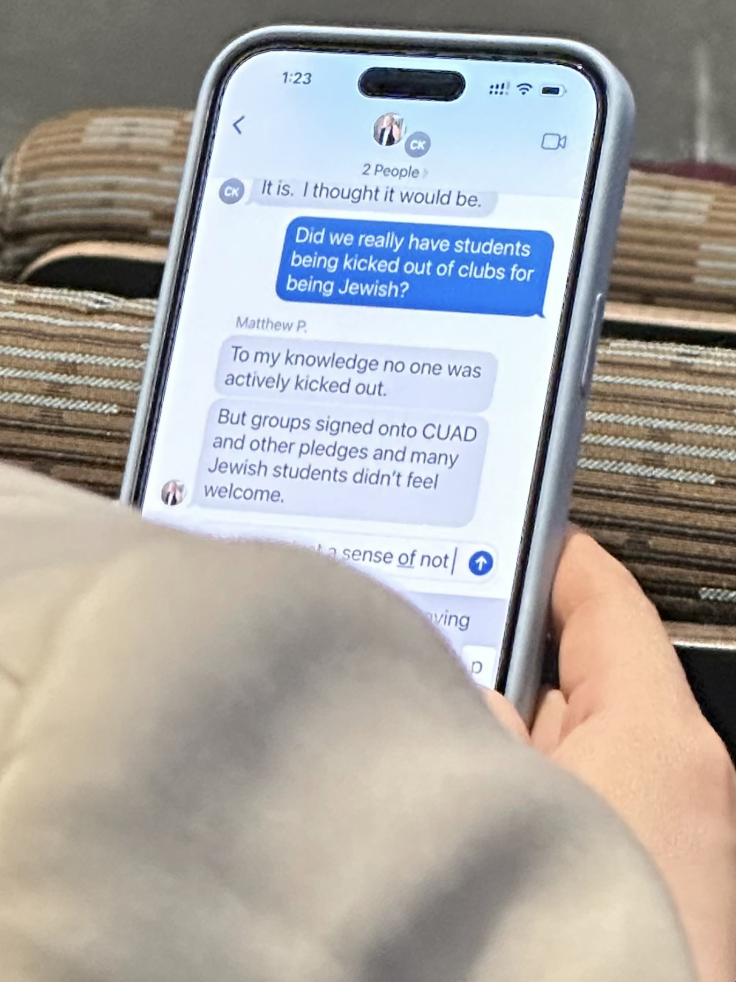

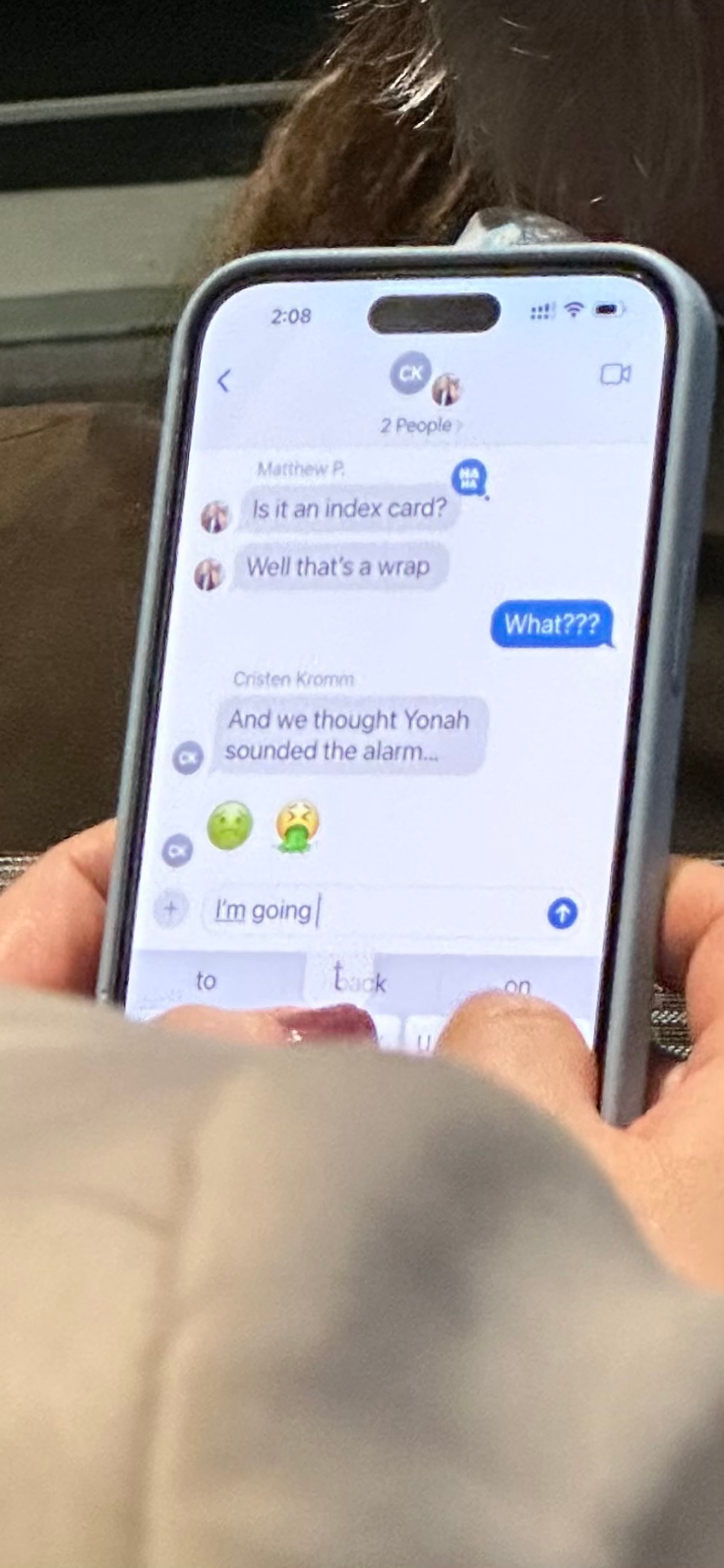

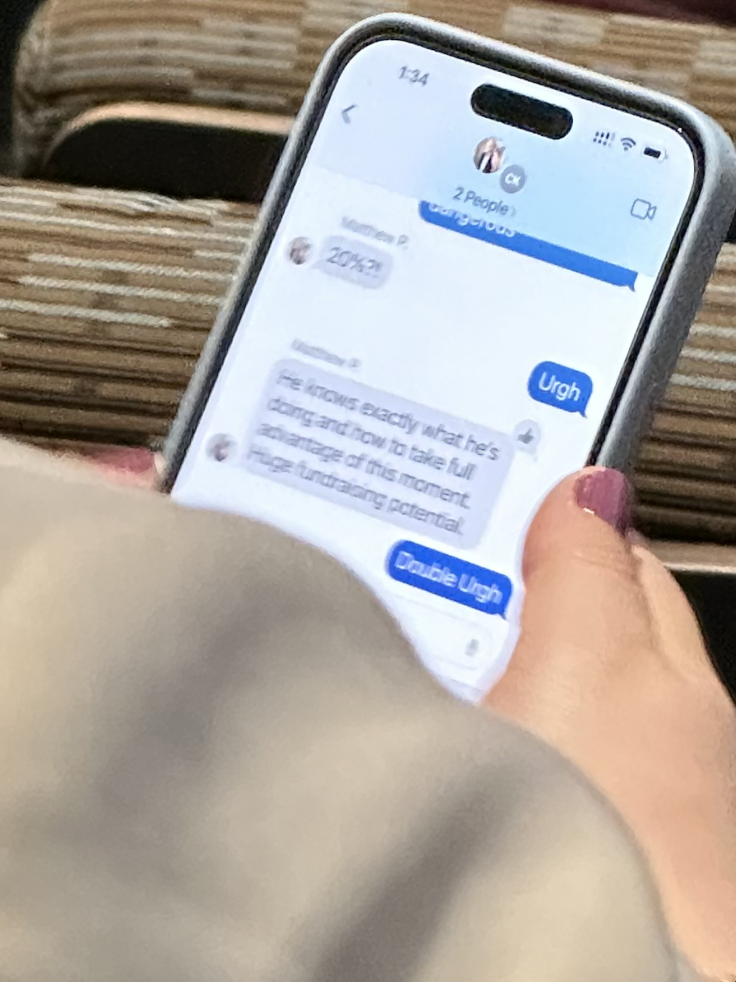

Throughout the panel, which unfolded over nearly two hours, Chang-Kim was on her phone texting her colleagues about the proceedings—and they were replying to her in turn. As the panelists offered frank appraisals of the climate Jewish students have faced, Columbia’s top officials responded with mockery and vitriol, dismissing claims of anti-Semitism and suggesting, in Patashnick’s words, that Jewish figures on campus were exploiting the moment for “fundraising potential.”

“This is difficult to listen to but I’m trying to keep an open mind to learn about this point of view,” Chang-Kim texted Sorett, the dean of the college. “Yup,” he replied.

The text messages, which were captured by an audience member sitting behind Chang-Kim who photographed the vice dean tapping away on her phone, also used vomit emojis to describe an op-ed about anti-Semitism by Columbia’s campus rabbi.

Chang-Kim’s messages and those of her colleagues are clearly visible in the photographs. The Free Beacon verified the authenticity of the photographs with the person who took them.

The text messages betray an attitude of ignorance and indifference toward the concerns of Jewish students on a campus where protesters have called to “burn Tel Aviv to the ground” and said that “Zionists don’t deserve to live.” The exchanges also raise questions about Columbia’s ability to combat anti-Semitism if its top administrators not only dismiss the problem but also sneer at those who speak out about it.

Sorett, Chang-Kim, Kromm, and Patashnick did not respond to requests for comment. An auto-response from Schizer’s email indicated he was offline for a Jewish holiday. The other panelists, Massel, Cohen, and Rottenberg, did not respond to a request for comment.

A spokesman for Columbia said the school is “committed to combatting antisemitism and taking sustained, concrete action to ensure Columbia is a campus where Jewish students and everyone in our community feels safe, valued, and able to thrive.”

The administrators expressed skepticism that Jewish students had experienced targeting or discrimination. As Massel, who published a news report in the Columbia Spectator about Jewish students who felt “ostracized,” was asked to dilate on “the experience of Jewish and Israeli students on campus,” Chang-Kim fired off a text to Kromm and Patashnick: “Did we really have students being kicked out of clubs for being Jewish?”

The messages are not time-stamped, so it is not always clear to what comments from the panel the participants are referring. In other cases, though, their references are easy to understand.

At one point, Kromm used a pair of vomit emojis to refer to an op-ed penned by Columbia’s campus rabbi, Yonah Hain, in October 2023. Titled “Sounding the alarm,” the op-ed, published in the Spectator, expressed concern about the “normalization of Hamas” that Hain saw on campus.

“Debates about Zionism, one state or two states, occupation, and Israeli military and government policy are all welcome conversations on campus,” the rabbi wrote. “What’s not up for debate is that massacring Jews is unequivocally wrong.”

As the panelists described the grim state of affairs for Jewish students on campus—one alumna broke down in tears describing her daughter’s experience as a Columbia sophomore—Kromm made a derisive reference to Hain’s column. “And we thought Yonah sounded the alarm…” she wrote to Chang-Kim and Patashnick.

Patashnick, the associate dean for student and family support, also chimed in to say that one of the panelists—it is not clear to whom he was referring—is capitalizing on the crisis at hand to raise money.

“He knows exactly what he’s doing and how to take full advantage of this moment,” Patashnick wrote to Chang-Kim and Kromm. “Huge fundraising potential.” Chang-Kim responded: “Double Urgh.”

Schizer, who joined Columbia University president Minouche Shafik and members of the school’s board of trustees in testifying before Congress in April, spoke both to Jewish students’ feelings of exclusion and to the administration’s failure to enforce its own rules over the course of the academic year as his colleagues texted in the background.

“To me, the very worst thing, which hasn’t gotten nearly enough attention … is the idea that you could be an undergraduate who is interested in dance, who wants to be in an LGBTQ-plus affinity group, who wants to play a sport,” Schizer said, “and all of a sudden you find out that actually, because you’re a Zionist and you’re proud of your ties with Israel, that you’re either explicitly kicked out or you’re just not welcome. And to my mind, that is utterly unacceptable.”

Massel added that Israeli students had “experienced anti-Israel sentiments their entire time at Columbia,” which “exponentially grew” after Oct. 7, leading them to leave campus for weeks.

Schizer, who served as co-chair of the university’s anti-Semitism task force, spoke bluntly about some of the university’s failures when it came to disciplining participants in unauthorized protests.

“We had some protests in the lobbies of academic buildings, and to me, that is just utterly unacceptable because this is a teaching university,” he said. “And you’re absolutely entitled to express your view, it’s just you can’t do it in a way that prevents people who are, frankly, paying a lot of money for these classes not to be able to hear what their professors are saying.”

“The university has to enforce its rules,” Schizer continued, but was “incredibly ineffective in enforcing its rules in the first few weeks. And I think that the fact that the university failed to enforce rules created the problem later.”

Among the comments Chang-Kim offered to Kromm and Patashnick: “This panel is really making the administration look like jokers.” Patashnick replied, “Yep.”