In its 2023 “Freedom in the World” survey, Freedom House documents that “global democracy has receded under pressure from authoritarian forces over the past 17 years.” It calls on democratic countries to be more active in advancing the cause of freedom.

In Foreign Policy, democracy scholars Ivana Stradner and Anthony Ruggiero pinpoint one cause of this retreat: “America is still losing the information war” — threatening world peace and democracy itself.

Winning that war involves action on many battlefronts. Technological superiority will not be enough. We must also recommit resources to the types of quiet diplomacy once associated with the United States Information Agency (USIA).

World leaders opposed to democracy do not await U.S. decisionmaking. They have already committed substantial resources to win internal and external battles in public opinion.

Witness Russian President Vladimir Putin’s continual efforts to create a false historical narrative within his own country, influence elections everywhere from Poland to the U.S., and flood social media across the world with disinformation. Or the scale of Chinese disinformation recently revealed to involve billions of dollars in “spamouflage” and outright intimidation online of critics in the West.

The losses to the U.S. are notable among potential friends, neutrals and even some traditional allies. The indifference of much of the non-Western world to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine reveals the startling decline in the soft power of the U.S. and the West.

This decline feeds on unchecked, often false, resentments that the U.S. and Western countries are indifferent to the effects of international economic crises, stack institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank against the non-West and fail to lead convincingly on widespread global problems.

This is not just a short-term battle. It is an investment, like an orchard, requiring constant attention, weeding and pruning to yield satisfying harvests. Today, we are reaping the bitter fruit of our past stinginess and neglect. In many places, we’ve lost foreign publics formerly disposed to giving us a sympathetic hearing because they experienced positive interactions with American outreach programs.

While many factors can lead a country to act in ways favorable to our strategic interests, repeated exposure over a long time to the openness, generosity and creativity that are persistent American cultural traits plays a part. Engagement abroad that built on these strengths used to be a major part of U.S. foreign relations. This work was the core mission of the former USIA and must be rebuilt.

On Oct. 1, 1999, in a post-Cold War economy move during the Clinton administration, USIA ceased to exist, with surviving programs assigned to the State Department. Lacking forceful advocacy in the executive branch, they were tucked into the State Department’s wings as “public diplomacy and public affairs.”

This bureau has since experienced the leadership of 17 persons — eight of whom served in an unconfirmed “acting” capacity. Most have been minor players in the nation’s foreign affairs establishment, with little say in either short-term or long-term efforts at soft-power diplomacy.

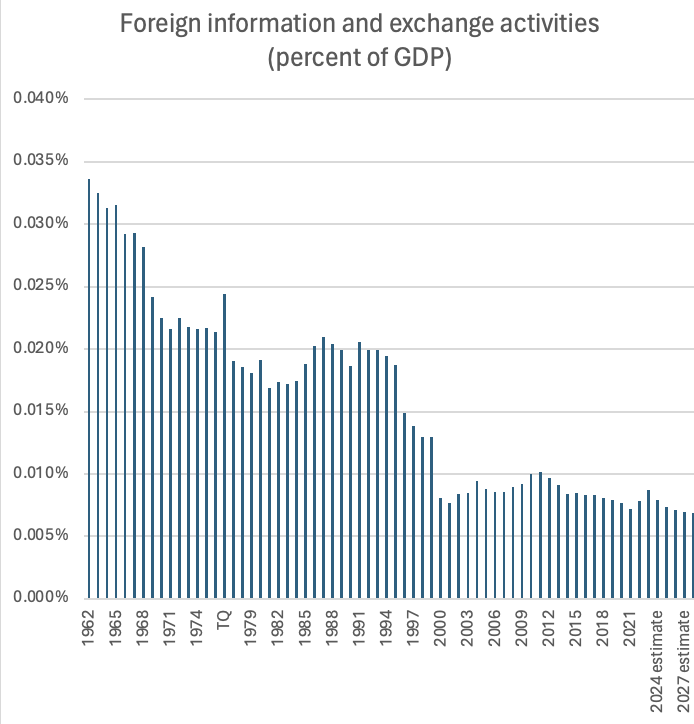

Admittedly, some of this is anecdotal. But the data are not. The federal budget’s foreign information and exchange activities have seen two dramatic drops from which they have never recovered. The first began in the early Vietnam withdrawal period in the late 1960s. The second ran from about 1994 to 2000, with the abandonment of the USIA occurring during that period.

Source: OMB Historical Tables

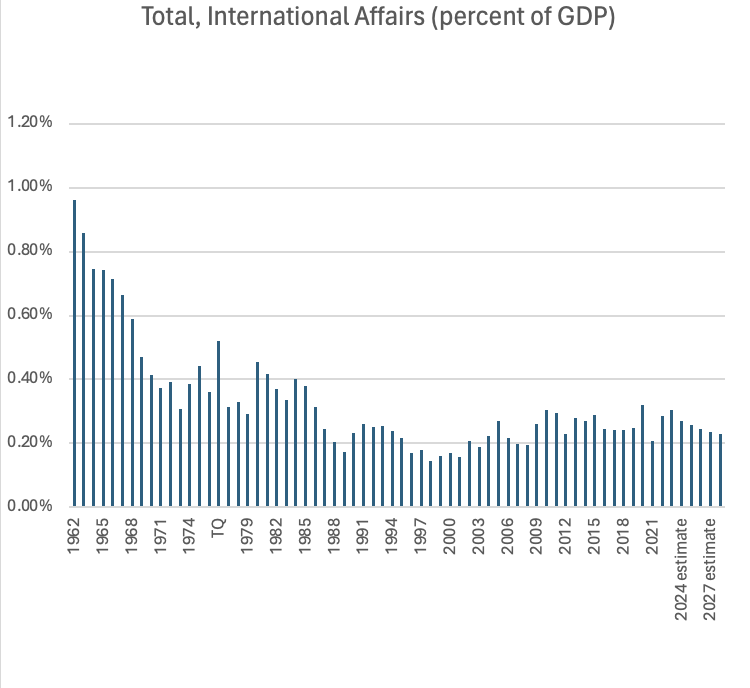

Of course, this was part of a larger decline in the total international affairs budget that stretched throughout much of the post-World War II era and hit a nadir in the years just before the Sept. 11 attack. Today, that budget sits at about one-fifth of 1 percent of GDP, as compared to a budget that, relative to GDP, was about 15 times larger during the Marshall Plan era.

Source: OMB Historical Tables

Winning internal budgetary battles in the never-ending information war with foreign adversaries has never been easy. There was a minimal domestic constituency for the broader objectives of “telling America’s story to the world” even during the Cold War, though the 9/11 attacks, the Ukraine invasion and recent Hamas terrorism against Israel have provided wake-up calls.

We are handicapped, too, by domestic polarization. Critics on the left often dismissed USIA as nothing more than propaganda that papered over American failings at home and abroad. Some on the right, like former Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) in his heyday, dismissed soft power as a mirage not worth pursuing.

It’s impossible, of course, to provide conclusive proof that some particular long-term effort was the direct cause of past success in expanding or at least protecting freedom and democracy. It doesn’t work in such an instantaneous or traceable way.

President Kennedy’s USIA director, the famous journalist Edward R. Murrow, used to stress on-the-ground presence through personal contact as “the last three feet” in an effective international exchange.

One of us was a public diplomacy officer in Latin American countries who saw the shriveling of once-flourishing binational cultural centers close doors of understanding for students and young people. Similar effects were seen in Germany when resources for the string of Amerika Haus cultural centers there largely dried up.

Despite school visits and teacher-training academies to counteract swelling misunderstanding and anti-American propaganda, there was never enough contact to change sentiments. And, after budget cuts, there was no backup supply of eager young foreign service officers to do the job.

Scaling up militarily to deal with even one fight, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, Ukraine or Gaza, absorbs many orders of magnitude more resources than required for public diplomacy to spread reliable information in foreign lands about our beliefs, intentions and more importantly, the enduring worth of open and free societies.

History almost certainly will record our laxity on this front — to the detriment of both our own and foreigners’ interests. Former Defense Secretary James Mattis, in 2017, summed up well the consequences overall of looming budget cuts:

“If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.”

C. Eugene Steuerle is a fellow at and co-founder of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center in Washington, D.C.