Donald Trump is not the first former president to launch a comeback campaign to return to the White House.

Martin Van Buren, Millard Fillmore, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover all attempted comebacks. Only Cleveland’s bid did not end poorly. Van Buren, Fillmore and Roosevelt unsuccessfully sought to regain the presidency as third-party candidates, while Grant and Hoover waged losing efforts to secure their party’s nomination.

Martin Van Buren, four years after losing his 1840 reelection campaign, was again the leading candidate to be the Democratic nominee before disclosing his opposition to the immediate annexation of Texas, where slavery would be allowed. Infuriated supporters of annexation at the party’s convention responded by successfully lobbying for a rule requiring a two-thirds majority to be nominated, dooming Van Buren’s chances. On the ninth ballot, the pro-expansionist James K. Polk secured the nomination.

Van Buren reluctantly became the nominee of the Free Soil Party in 1848 after a decision by the Democratic Convention left his home state of New York without a voice in the proceedings. Although the Free Soilers were only on the ballot in 17 of 29 states, he accepted the party’s nomination anyway, because it brought together individuals who had always been on different sides of issues in a united effort to prevent expansion of slavery into those territories “exempt from that great evil.” The former president got just 10 percent of the popular vote and no electoral votes.

Vice President Millard Fillmore ascended to the White House following President Zachary Taylor’s death in July 1850, but decided not to seek a full presidential term in 1852. Four years later, the ex-Whig changed his mind and accepted the nomination of the short-lived Know-Nothing Party, which was anti-immigration and anti-Catholic.

Fillmore became the “leader of a party dedicated to nativism,” historian Robert J. Rayback says, because he believed it “might become the rallying point for a strong and truly national party,” and ease the growing sectional bitterness between North and South. Though handily defeated, Fillmore did capture more than 20 percent of the popular vote, and won Maryland’s eight electoral votes.

Ulysses S. Grant’s failed attempt to gain another Republican nomination in 1880 was prompted by his concerns over the rise of ex-Confederates in the South who sought to undo the “results of the war” and everything that he had accomplished as president. Grant, writes Ron Chernow, “feared that unreasoning southern resistance to northern capital doomed the region to economic stagnation.”

Grant had also been “rejuvenated by his renewed popularity at home,” and eager to bring about a more international role for the U.S. following his 18-month global tour after leaving the White House. On the 35th ballot at the June 1880 Republican National Convention, the anti-Grant forces within his own party were able to deny him the nomination, instead choosing James A. Garfield.

Following his 1888 defeat, Grover Cleveland initially seemed indifferent about a political comeback. He worked for a prestigious New York law firm and vacationed frequently on Cape Cod. During the first two years of President Benjamin Harrison’s term, however, Cleveland became increasingly worried about government spending and passage of the McKinley Tariff and Sherman Silver Purchase Act by the Republican-controlled Congress.

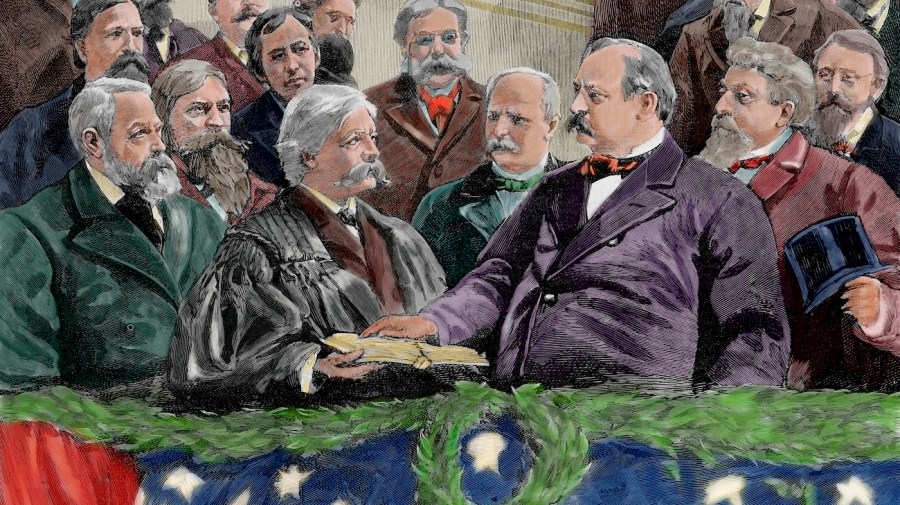

After the Democrats gained 93 House seats in the 1890 midterm elections, Cleveland began to behave more like an interested candidate. In February 1891, his name was thrust back into the spotlight and ultimately a rematch with Harrison when he blasted unlimited silver coinage as a “dangerous and reckless experiment” in a letter to a meeting of reformers. That November, Cleveland defeated Harrison and Populist Party candidate James B. Weaver to become the only president elected to discontinuous terms.

Harrison’s loss marked the second time an elected president lost the popular vote twice, the first being John Quincy Adams in 1824 and 1828. This feat was not repeated until Trump lost the popular vote in 2016 and 2020.

Late in February 1912, four years after declining not to run again, Theodore Roosevelt —increasingly frustrated with the policies of his hand-picked successor William Howard Taft — tossed his hat into the ring as a candidate for another term. He felt his immense popularity “created the possibility of a unique political opportunity” to win the “extraordinary power” needed to achieve the Progressive reforms “America so desperately needed,” which special interests had used the courts and Congress to block.

Roosevelt was the clear favorite in the Republican primaries, but Taft’s control of the party organization was too much to overcome at the convention. Roosevelt then accused the GOP of corruption and launched a third-party campaign for president under the Progressive Party (or Bull Moose Party). The rift between Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote, allowing Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson to win the election.

In 1936, Herbert Hoover, “anxious for vindication and a chance to ‘debate the issues,’” hoped a deadlocked Republican convention would turn to him to lead the battle against Democratic incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt. He traveled across the country defending his ideas while denouncing the New Deal. The GOP, however, instead turned to front-runner Gov. Alfred M. Landon of Kansas, whom FDR defeated in a landslide.

When speculation of another Hoover candidacy began gaining momentum in 1940, “he felt an open quest for the nomination would be undignified,” and once again “his hopes depended on a deadlocked convention.” His last futile effort at another nomination essentially ended with the 32 votes he received on the third ballot at that convention. Three ballots later, Wendell Willkie — “who lacked Hoover’s assets but also lacked his liabilities,” in the words of historian Glen Jeansonne — became the Republican nominee.

Donald Trump might become another Cleveland — or he may suffer the same fate as Van Buren, Fillmore, Grant, Roosevelt and Hoover. Trump is now the presumptive Republican nominee. The outcome of forthcoming events will decide how history records his attempt to regain the White House.

Stephen W. Stathis was a specialist in American history with the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress for nearly four decades. He is the author of “Landmark Debates in Congress From the Declaration of Independence to the War in Iraq” and “Landmark Legislation: Major U.S. Acts and Treaties.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.