It was the fall of 1980, and the ex-members of the Beatles were engaged in a cold war — largely with John Lennon.

A decade after the legendary band’s toxic implosion, George Harrison described his notoriously temperamental band mate as a “piece of s–t.”

“He’s so negative about everything,” Harrison, typically known as the quiet one, said of Lennon. “He’s become so nasty.”

The usually diplomatic Paul McCartney aired out his own bitter grievances at Lennon — his beloved boyhood friend and longtime writing partner — and wife Yoko Ono.

“The way to get their friendship is to do everything the way they require it,” McCartney bristled about the couple. “To do anything else is how to not get their friendship. I know that if I absolutely lie down on the ground and just do everything like they say and laugh at all their jokes and don’t expect my jokes to ever get laughed at … if I’m willing to do all that, then we can be friends.”

Even affable Ringo Starr admitted that he was actually “pleased” when the Beatles officially announced their April 10, 1970, split, following weeks of hostile infighting in and out of the recording studio.

“It was time,” Starr said. “Things only last so long.”

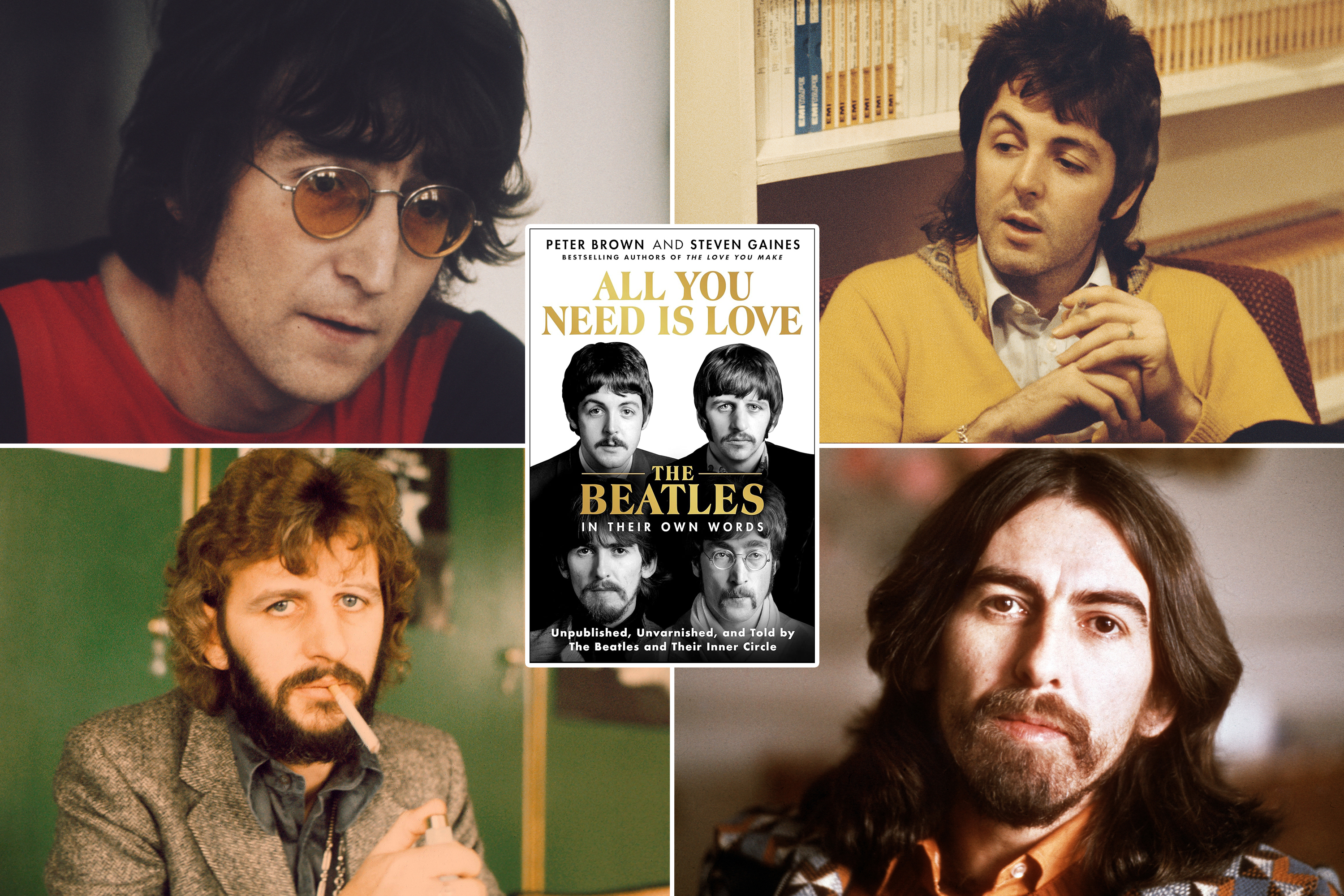

Those are just a few of the revelations found in the new book “All You Need Is Love: The Beatles in Their Own Words” (St. Martin’s Press), an illuminating page turner from former band aide Peter Brown and best-selling author Steven Gaines.

The extensive oral history is made up of candid interviews with Gaines, captured in 1980-1981; a scheduled sit-down with Lennon never happened before his Dec. 8, 1980, assassination. Besides the surviving Beatles, the author spoke with the band’s wives, lovers, friends, business associates and hangers-on.

“All You Need Is Love” is a sequel to the 1983 biography “The Love You Make: An Insider’s Story of the Beatles,” which gave an unprecedented look behind the curtain of their meteoric rise, groundbreaking run and toxic breakup — including drug use (amphetamines, marijuana, LSD, cocaine, heroin) and dalliances with prostitutes and groupies.

This time around, the subjects paint a troubled portrait of how fame itself came to ruin the biggest band in the world.

Starr offers a harrowing account of the Beatles’ 1966 tour in Manila where the band was “spat on” and nearly held hostage after turning down an invite by Philippines’ President Ferdinand Marcos and First Lady Imelda Marcos.

“So we get to the plane, and there’s an announcement that our press man, Tony Barrow, and [road manager] Mal Evans had to get off the plane,” said Starr, adding a more disturbing layer to the often-told story. “We thought, now they’re taking us off two by two to shoot us.”

By the time the Beatles were done with the US leg of their ’66 tour they were cracking up.

“We kept realizing we were getting bigger and bigger until we all realized we couldn’t go anywhere – you couldn’t pick up a paper or turn on a radio or TV without seeing yourself,” said Harrison. “It became too much.”

The celebrated partnership of Lennon and McCartney is also examined, chronicling how the two close lads from Liverpool went from collaboratively penning such classics as “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” “Eleanor Rigby” and “A Day In the Life” to waging an ugly battle over control of the group’s Apple company.

“I suddenly had more Northern Songs shares than anybody,” admitted McCartney, referencing the duo’s song publishing company, “and it was like oops, sorry. John was like, ‘You bastard, you’ve been buying behind my back.’”

Former Apple Records president Ron Kass insisted that the bad blood that eventually drowned the band could have been avoided if he “would have presented [Lennon] with a bag of money every once in a while.

“Money invested was too abstract for him,” Kass said of Lennon.

Things came to a head when Lennon installed Allen Klein as the Beatles new manager in early ’69. McCartney wanted nothing to do with the infamous figure he called a “devil,” who he later accused of stealing millions from the band, saying of his bandmates: “the three of them wanted to do stuff, and I was always the fly in the ointment.”

But the majority ruled in the Beatles — and McCartney was incensed when Starr voted to hire Klein. “Then I said, ‘Well, this is like bloody Julius Caesar, and I’m being stabbed in the back.’”

He accused Klein of winning over Lennon by cozying up to his controversial wife, Yoko Ono.

“Klein saw the Yoko connection and told Yoko that he would do a lot for her,” McCartney recalled. “And that was basically what John and Yoko wanted: recognition for Yoko.

Bad feelings intensified after the bassist was pushed to delay his solo album “McCartney” to make room for the band’s final release, “Let It Be.”

When Starr made a visit to his home in an effort to make peace on behalf of the group, McCartney kicked out the drummer.

“I remember he was the only person I’ve ever told to get out of my house,” said a regretful McCartney. “That was the worst moment with Ringo, and I felt sorry for him because it really brought him down, you know.”

A year later, on Dec. 31, 1970, McCartney sued his bandmates for dissolution of their partnership.

The Beatles’ entangled personal lives were just as dysfunctional.

Over the years, much has been made of how Eric Clapton wooed and eventually stole George Harrison’s wife Pattie Boyd, even writing the song “Layla” about his (then) unrequited love for her.

But Harrison was just as guilty of falling for a friend’s spouse.

Starr’s first wife, Maureen Starkey, recalled Harrison’s scandalous pursuit of her in the ‘70s.

She and Starr had just hosted Harrison and Boyd for dinner at their home. “I was cleaning the table,” Starkey said. “[Harrison] picked up a guitar and started to sing a song … and then he just turned to [Starr] and said, ‘I’m in love with your wife.’ I was totally stunned.”

Asked if Harrison was out of his mind with such a pronouncement, she replied: “Jesus Christ, yeah.”

As for the proverbial elephant in the room, Ono, she doesn’t hide from her critics or long-standing accusations that she was the root cause of the band’s break-up.

“Everything we did in those days, anything that was wrong, was my responsibility,” Ono said, with Harrison even blaming her for putting Lennon on to heroin.

Not that she didn’t provoke it.

Ono joked about the time she attended a Beatles meeting with a roomful of Jewish businessmen — and she dressed in Arab garb.

“They hated me anyway,” Ono mused. “But yeah, that made it worse. Funny.”

In the end, it was hard to blame the band’s break-up on any one thing. Ono cites Lennon’s use of heroin; Gaines notes that Lennon “weaponized” his wife, making her his bad cop. It’s obvious in the book that, as Gaines writes, “John and Paul had already had enough of each other.”

Siad McCartney: “I think it was just that we were growing apart.”

Still, he details a telephone call he had with Lennon on Christmas day of 1979 as “pleasant.”

“I’ve read cracks about, ‘Oh the Beatles sang, “All you need is love” but it didn’t work out for them,’” Lennon said in a 1972 quote used as an epigraph for the book. “But nothing will ever break the love we have for each other.”