An incredible thing happened this week.

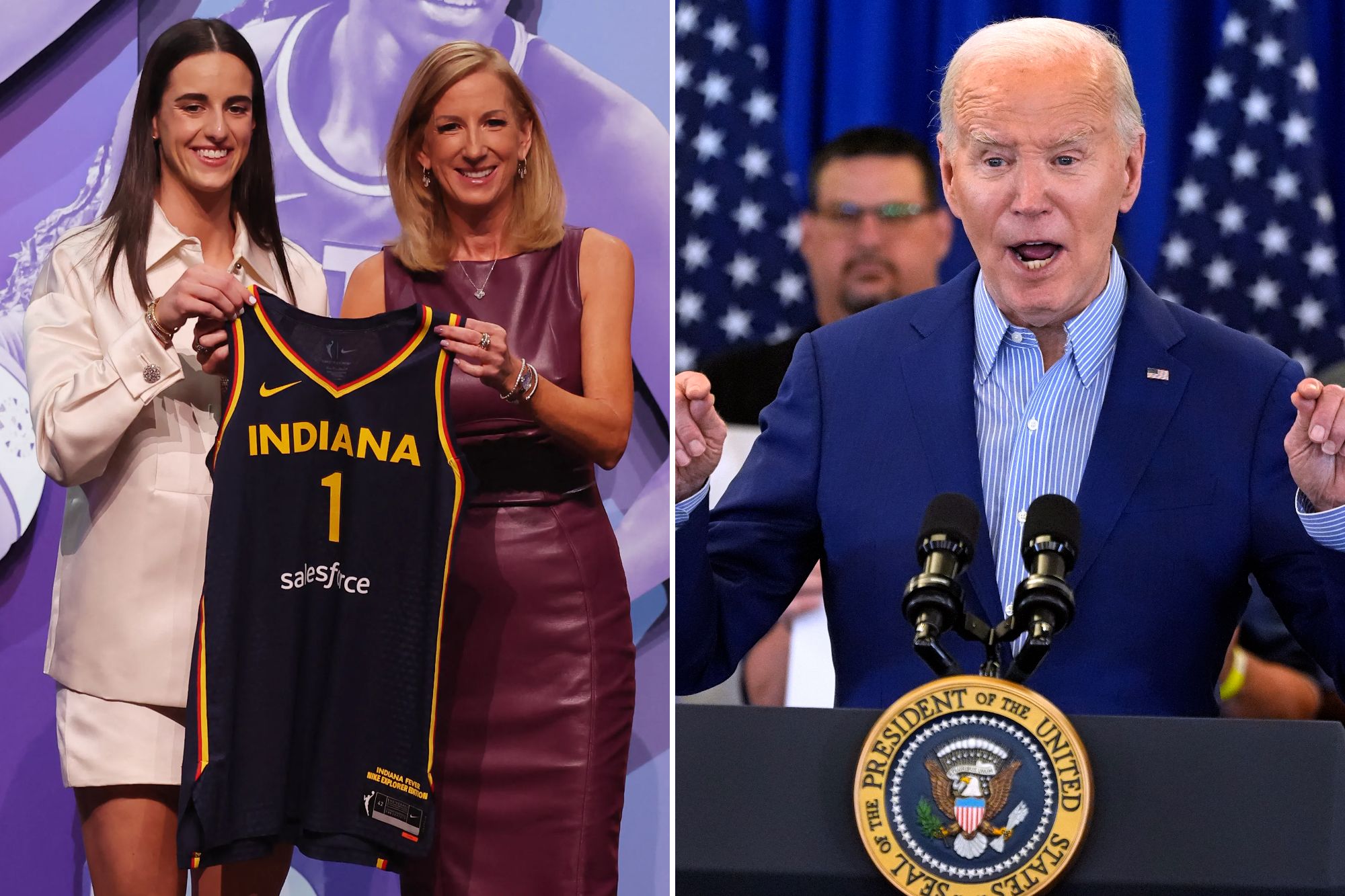

A whopping 2.45 million people watched the WNBA draft Monday, as University of Iowa shooting sensation Caitlin Clark — dressed in head-to-toe Prada, the only time the label has ever dressed an athlete for a basketball draft — was selected first overall by the Indiana Fever.

Last year, an audience of 500,000 tuned in — that’s an 80% increase in viewers.

And they all seemed shocked to learn the truth about WNBA salaries, especially rookie ones.

Despite her captivating play, astounding range and marketing prowess, Clark will only earn $338,056 over four years: $76,535 annually.

Victor Wembanyama, the No. 1 pick in the 2023 NBA draft, will make $55 million for the same number of years.

Outraged over the pay disparity bubbled up everywhere: on social media, morning television and even at the White House.

“For somebody who is now the face of women’s basketball, it seemed kind of ridiculous,” Hoda Kotb said on the “Today” show, adding that it was “disturbing” and “like picking at an old scab for many women.”

Kotb’s co-host, Jenna Bush Hager, called the gap “so jarring … We’re talking about equal pay. That ain’t even close.”

Joe Biden put aside his vanilla ice-cream cone long enough to weigh in on X with pandering platitudes — the likes of which we haven’t seen since Kamala Harris foolishly claimed that women ballers didn’t get NCAA tournament brackets until 2022.

“Women in sports continue to push new boundaries and inspire us all,” Biden wrote. “But right now we’re seeing that even if you’re the best, women are not paid their fair share. It’s time that we give our daughters the same opportunities as our sons and ensure women are paid what they deserve.”

Perhaps he can enlist his son Hunter to pull a few strings and land the league a Burisma sponsorship.

But, seriously, how do you define fair?

Instead of blaming the pay gap all on the evil forces of the patriarchy, or inferring that women always get the short end of the stick, we should be asking questions about the sports landscape and how money flows from television deals and ticket sales.

The league is a complicated business with a tough bottom line — not a charity dedicated to gender equality.

According to Front Office Sports, the WNBA currently makes $60 million a season from its TV contracts, while the NBA makes $2.7 billion annually.

If there is a large group of people and only one chicken in the pot, not everyone gets a hearty portion. You get what you get. And the WNBA, which was established in 1996, has traditionally not had a lot of chickens in the pot.

Remember when Phoenix Mercury star Brittney Griner was held in a Russian prison for eight months on a narcotics charge back in 2022? She wasn’t there to stock up on nesting dolls. Griner was playing for UMMC Ekaterinburg, which paid her over $1 million a season.

Many other WNBA stars, including Diana Taurasi and Sue Bird, have gone overseas to play. Since the WNBA only plays a four-month season (half of the NBA’s), athletes have time to play in two leagues — and Russia, like it or not, is where they can earn real money.

Unlike the NBA, which has been around since the 1940s, the WNBA has just over a quarter-century under its belt. It’s growing, but monetary success is not ready-baked into the league. And the men’s and women’s contracts are structured differently.

Clark’s entry — along with that of bright stars like Angel Reese, Kamilla Cardosa and Cameron Brink — is a profound milestone.

Thanks to NIL, many athletes will come out of college with a fan base, name recognition and some nice endorsements. Don’t weep for Clark, who is reportedly set to sign a seven-figure sneaker deal and leave Iowa with an NIL valuation of $3.4 million, according to On3.

Steelers quarterback Russell Wilson shared a post on X saying: “These ladies deserve so much more … Praying for the day.”

But Wilson, who knows all too well the financial realities of sports, shouldn’t be praying. He should be paying — and urging others who are outraged to do the same.

If all these new fans want to reward WNBA players, they need to invest: Attend the games, watch the teams on TV, buy the jerseys — then maybe the league and the teams will make real money to reward athletes.